Among the many issues Mary I had to deal with once she became Queen of England was the funeral for her half-brother King Edward VI. Edward died on July 6, 1553 at Greenwich after a long and painful illness. His death was kept secret for three days while some noblemen and councilors put into motion a plan to elevate Lady Jane Grey to the throne. Mary Tudor, daughter of King Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon had something to say about this plan. After declaring herself queen and raising an army, Mary entered London with no bloodshed and was proclaimed queen on July 19 while Jane Grey languished in the Tower of London.

Edward’s body had been embalmed and sealed in a lead coffin to await burial. Mary had an enormous dilemma on her hands. As queen, she was the head of the church in England and the only legal form of worship was according to the Book of Common Prayer of 1552. Mary was highly motivated to return England to the Church of Rome and would have preferred to have Edward’s service be the traditional Catholic liturgy. Edward had been brought up in the reformed Church of England and was therefore considered a heretic and schismatic by the Catholic Church. It would not be inappropriate to bury him with the old liturgy.

The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who was Mary’s cousin, and the Imperial ambassadors at the English court were rightly worried if Edward was buried with a Catholic service, those of the reformed persuasion would be incensed. There could even be a violent reaction, especially in London. The Imperial ambassador Simon Renard came up with a compromise. Edward would be buried according to the Book of Common Prayer. Protocol did not require the dead monarch’s successor attend the funeral so Mary did not have to risk eternal damnation by attending the unorthodox service. Mary was at liberty to organize a traditional service for her brother at another location.

Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury and author of the Book of Common Prayer would officiate the service and the procession would be in a style similar to that of the funeral for King Henry VIII. Edward’s body was taken by barge to Whitehall. The night before the funeral he was transferred to Westminster Abbey accompanied by a traditional procession including a large gathering of choirboys in surplices, singing clerks and twelve of King Henry VIII’s beadsmen (ones who say prayers for another; a humble servant) from the former Observant Franciscan (Greyfriars) church at Greenwich.

Nine members of Edward’s retinue followed. They were all dressed in black and carried banners with the heraldic emblems of his ancestry. These included the red Welsh dragon of Cadwallader and Owen Tudor, the Lancastrian greyhound and the lion of King Henry VIII. Three heralds came next carrying Edward’s helmet and crest, his shield, sword and Garter and his armor.

Behind these men was the coffin draped in blue velvet on a cloth of gold covered chariot pulled by seven horses draped in black velvet down to the ground and decorated with escutcheons. A canopy of blue velvet was carried above the coffin. On top of the coffin was a life-size effigy of Edward, carved by the Italian sculpture Niccoló Bellini. The effigy was holding a scepter and had on a crown, the collar of the Order of the Garter and a Garter ribbon on the leg. Surrounding the coffin were the standards of the Tudors, the Seymours and the Garter. The chief mourner was the lord Treasurer, Sir William Paulet, Marquess of Winchester. He rode behind the coffin on a horse draped on black velvet. The master of the horse rode behind him on a horse trapped in cloth of gold. This was followed by another man in a suit of armor riding a horse. Both the armor and the horse were later given to the church. After this, there were nine hooded henchmen on horses draped in black velvet.

As the coffin passed in the procession, the people moaned, cried and lamented as was expected in that era. Once the body was in the Abbey, it was placed on a hearse draped in seventy two yards of black velvet, surrounded by tapers on thirteen branched stone pillars, representing the traditional burning chapel of medieval and early modern Catholic royal obsequies. In comparison, King Henry VIII had only had nine pillars. The walls and aisles of the Abbey were covered completely in black cloth.

Archbishop Cranmer presided over the Reformed service as written in his prayer book although the celebration of the Holy Communion was made in addition to the customary rites. The night before the funeral Queen Mary had commanded the service of the dead be performed in her chapel in Latin, as is the custom in Rome. Concurrently with Cranmer’s service, a requiem mass was conducted by Stephen Gardiner, bishop of Winchester in the Tower of London. Mary was present for this service. Masses were said over two more days in the Tower and many Londoners were amazed this had occurred.

Edward’s body was lowered into a white marble vault in front of the altar made by Pietro Torrigiano for Edward’s grandfather King Henry VII’s tomb. In 1573, plans were put forward for a tomb for Edward. William Cure of Amsterdam imagined a Franco-Italianate monument made of marble and bronze decorated with crowns imperial, Tudor roses and fleur-de-lis. The idea was to build this next to King Henry VIII’s place of burial in St. George’s chapel at Windsor.

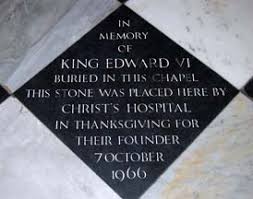

But, plans for a magnificent tomb for Henry VIII were never finished and construction of Edward’s tomb was never started. The altar of King Henry VII’s Lady Chapel in Westminster was destroyed by the Puritans in 1644. When workmen were investigating a place to bury King Charles II in 1685, they found Edward’s marble vault. In the 19th century, Dean Stanley of Westminster Abbey viewed Edward’s coffin and wrote down the Latin inscription: “Edward the sixth by the Grace of God King of England, France and Ireland, Defender of the Faith and on earth under Christ supreme head of the Churches of England and Ireland and he migrated from this life on the 6th day of July in the evening at the 8th hour in the year of our Lord 1553 and in the 7th year of his reign and in the 16th year of his age”. A new stone was placed over the vault in 1966 with the inscription: “In memory of King Edward VI buried in this chapel this stone was placed here by the Christ’s Hospital in thanksgiving for their founder 7 October 1966”. This can be seen to this day.

Further reading: “Edward VI: The Lost King of England” by Chris Skidmore, “Edward VI” by Jennifer Loach, “Mary I: England’s Catholic Queen” by John Edwards

[…] vault where Henry VII, Elizabeth of York and James I are buried. In the same area is the grave of Edward VI. There is no monument for Edward, only a plaque in the floor. Also buried here is Anne, the […]

LikeLike

[…] Origen: The Funeral of King Edward VI « The Freelance History Writer […]

LikeLike

Not surprised Henry VIII had beadsmen. Many assume Henry was just as ardent a Protestant as his son, Edward VI. Not so. Henry abolished certain old church practices, but kept a good many more than generally assumed.

“Defender of the Faith” was a title bestowed by the Pope before the Anne Boelyn matter. Henry was ardent in his faith, and dedicated to the daily chapel, prayers, & etc. that he practiced all is life. He just eliminated what he considered heretical and/or superfluous. Most English intellectuals were admitting monastic life was rife with corruption & had long ceased doing holy work. They questioned the reasons for many rites & rituals, believing they had the right to read & discern God’s word for themselves. They doubted the need for saintly intervention. They thought the church was fat, lazy, & too rich. No Christ-like sharing. Just greedy, corrupted, & rotting from within.

Many of the commons were of similar feeling, but would have preferred keeping the church intact & REFORMING it from within. The church was security for the soul, and sometimes provided protection, from rapacious overlords. Give the church’s power to the King, and fearful vulnerability could increase.

Though Henry was actually more Roman Catholic than he was a Protestant reformer, he seemed to pay scant heed to Edward’s spiritual education. Doubtless, he trusted Cranmer & was in such pain & misery from his infectious leg & other issues that he took it for granted his son’s spirituality was in good hands. Add the encouragement from Queen Catherine Parr, and Edward was tacking a very different course from his father’s.

But Henry’s church was embryonic, changing rapidly, and far from coalescing a set liturgy or even a core of beliefs. That would come when Edward ascended.

And there was little time for Edward VI. I personally believe he was poisoned over a period of years. Whether by design or by the lifestyles and medical practices of the times, the closer Edward came to death, the more the efforts of the reformers were ramped up to establish the Protestant Church of England. Those efforts cost Cranmer & many others their lives. Mary had other plans. Elizabeth observed it all & chose a more moderate course.

Thank you, Ms. Abernethy, for this well-written account of Edward’s funeral!

LikeLike

Fascinating account, I love reading articles like this

LikeLike