The Freelance History Writer is pleased to welcome back Richard Taylor to the blog. He lives near Manchester, England and has a lifelong interest in monasteries, visiting many across the UK and Europe. Although his degree is in Aerospace Engineering, he has completed various Art History courses on-line through Oxford University Continuing Education. You can check out his blog here. He has a new book coming up soon: A Thousand Fates: The Afterlife of Medieval Monasteries in England and Wales.

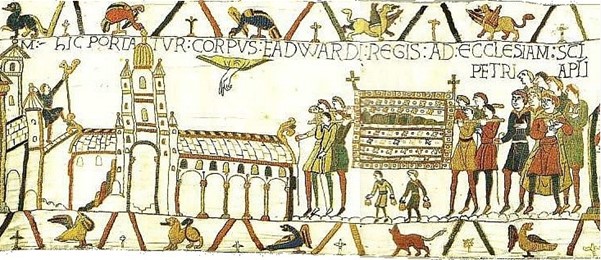

On the feast of the Epiphany 1066, King Edward the Confessor’s funeral took place at St Peter’s Abbey, Westminster, an event captured on the Bayeux Tapestry. Today we think of Westminster Abbey as the chief English royal mausoleum. However, after the interment of Edward the Confessor, it was to be over two hundred years before another English king would be buried at Westminster – Henry III in 1272. Those successors of Edward’s free to choose had chosen their own customised burial locations elsewhere.

Although subject to significant spoliation, Edward the Confessor’s tomb at Westminster still contains the remains of the saintly monarch. However, of his seven successors, five of them are missing (Harold II, Henry I, Stephen, Henry II and Richard I). A sixth, William II, is possibly partly amongst a jumble of other royal bones in a casket at Winchester Cathedral and the seventh is William the Conqueror whose tomb in Caen was ransacked during the French Wars of Religion leaving just one thigh bone now under a restored stone slab.

Harold Godwinson, who took the crown after Edward the Confessor, was allegedly buried in Waltham Abbey, Essex. Harold had founded a college at Waltham in thanksgiving for being cured of paralysis through the miraculous intercession of the local relic – the Holy Cross. According to a history of Waltham, ‘De Inventione Sanctae Crucis Walthamensis’ written in the late 12th century, two canons from the college accompanied Harold’s mistress, Edith Swan-neck, to the battlefield at Hastings. There amongst the heaps of Saxon dead, she identified him.

The earliest account of the conquest was written contemporarily with the invasion by Bishop Guy of Amiens. In this version, Harold’s corpse was carried to the Norman camp next to the sea. His mother pleaded for the return of the body in exchange for its weight in gold. William refused thinking it unseemly that Harold should be buried according to his mother’s wishes whilst so many lay strewn about the battlefield. He called Harold a usurper and those Englishmen had died to support his avarice. According to Guy the last Saxon King was placed under a stone cairn on a cliff top so that he ‘may still be guardian of the shore and sea’.

Victorian historian Edward Freeman proposed that Harold was initially buried under the cairn and then translated to Waltham after William had been crowned in December 1066. With the throne secure, the Conqueror could allow Harold’s interment in hallowed ground. In the late 12th century, Henry II undertook a dramatic transformation of Waltham Abbey. The church was enlarged significantly, and Harold’s tomb apparently relocated to retain its high-status position near the High Altar in the new presbytery. In ‘De Inventione’ written around the same time, the author recalls being present at the re-interment. Following Waltham’s dissolution about two-thirds of this enormous church was demolished leaving the nave alone to serve the parish, a function it still undertakes. Hence, with the presbytery gone the site of the high altar and the supposed tomb lie in the open air.

Various grand tombs have been unearthed but with no conclusive connection to Harold. In the late 16th century, the new owner of the Abbey, Sir Edward Denny resolved to level out the ‘ruinous heaps’ that resulted from the Presbytery’s destruction. During this operation, his gardener found ‘a fair marble stone’ with an intact skeleton underneath but this marble cover was inscribed with a cross fleury indicating that the incumbent was probably an abbot. Other tales also lack provenance – an inscription on the grave of a James Raphael recalls that he was buried in 1686 ‘in Harold’s tomb’ and in 1786 a Purbeck marble coffin was found, its attendant skeleton turning to dust on exposure.

Was Harold actually buried at Bosham, Sussex? The port had connections with the Godwin family and Harold is pictured in the Bayeux Tapestry praying in its church before his trip to Normandy. In 1954 a headless skeleton was found under the floor of the church in a stone sarcophagus. Recently the parish applied for its exhumation to enable scientific analysis, but the diocese refused permission as ‘the prospect of obtaining a meaningful result is so remote in this instance’.

In another story, Harold flees the battlefield much wounded and is returned to health by the ministrations of ‘a Saracen woman’. He headed for the continent initially to drum up support to retake his kingdom but eventually he resorted to touring the great shrines including Rome. Ultimately, he came back to England and lived out his years as a hermit in Chester where he was buried. Curiously this story (‘Vita Haroldi’, 1216) formed part of Waltham’s library of manuscripts even though it contradicts the ‘Inventione’ which placed Harold in their own church.

Notwithstanding the doubts, today a stone tablet lies in the grounds of Waltham marking the location of the high altar with a small pillar behind on the site of Harold’s alleged grave. Harold and Edward V are the only kings after Edward the Confessor whose original resting places are unknown.

After William I’s death, his third son William Rufus succeeded him. Rufus was killed by an arrow whilst hunting in the New Forest in August 1100. It was probably an accident but naturally conspiracy theorists filled the void with tales of murder particularly as his hunting party had fled the scene. This party included his brother Henry who hastily secured the crown for himself. It was left to local countryfolk to deal with the dead king, and he was brought to Winchester on a charcoal-maker’s cart.

Winchester had been capital of Saxon England and many of its rulers had been interred close to St Swithun in the original Cathedral Priory. An enormous new Norman version had not long been completed when Rufus was laid to rest reputedly in a plain, flat-topped marble tomb under the central tower. This tower collapsed in 1107, an event attributed to William’s troubled relationship with the church. What happened to him next is not clear, not helped by vagueness in the sources about the location of tombs and changes to the cathedral’s floor level.

The Purbeck marble cambered top monument which still lies in the choir had been attributed as the ‘Rufus Tomb’. This was opened in 1868 and a nearly complete but heavily damaged skeleton was found with some fragments of grand clothing. Also present was a metal spear-like object which the investigators thought could be the arrowhead that had killed Rufus. However, the grand clothing is now thought to be more ecclesiastical than royal particularly that of an apparently hastily buried king. Hence, the occupant is believed to be Bishop Henry of Blois (the skeleton is also too tall for the ‘nasty, brutish, and short’ Rufus) and the spear-like object could be part of his crozier. Henry was brother of King Stephen and one of Europe’s most powerful prelates. He was also Abbot of Glastonbury and a major patron of art and architecture in a period known as the 12th century renaissance. He had done much to enhance the esteem of the diocese and hence was a more suitable candidate for this prime location than the tyrannical king who had at one time appropriated the cathedral’s revenues for himself.

In 1158 Bishop Henry had moved the remains of the Saxon and Danish rulers of England from the demolished Saxon cathedral into mortuary chests which were displayed prominently in the Norman one. These chests were renewed in the 16th century, and it is believed that at this point William’s bones were relocated to one of them. He now shared a casket with several others including Cnut and his wife but where he had been in the intervening 400 years is not clear. The contents of these caskets were scattered during the Civil War, the bones used as missiles to break remaining stained glass. Those bones left were gathered together after the restoration and put back in the caskets.

Rufus’ brother Henry I was less inclined to treat England as a Norman colony and did much to develop the infrastructure of government. He aimed to create a dynastic mausoleum at his vast foundation of Reading Abbey. This became one of England’s richest monasteries regularly hosting royal occasions due to its facilities and strategic location on the route west from London. Henry died in Normandy after over-indulging on his favourite fish. Most of him was brought to Reading in a bull’s hide and was laid to rest in front of the high altar. Despite its royal connections none of Henry’s successors were buried at Reading.

Following dissolution in 1539, the Abbey’s treasure and lucrative estates were quickly dispersed but its buildings lingered. The Abbot’s Lodgings (probably one of England’s finest examples) became a royal palace. Unlike most other monasteries, the rest of the complex endured for ten years after its closure, the neglected buildings slowly deteriorating. However, they could not survive the attentions of the rapacious Duke of Somerset who was granted Reading by his nephew Edward VI. A detailed account of the piecemeal sale of the abbey’s fabric survives with much of the stone and roof timber helping to restore the nearby parish church of St. Mary’s. Over four hundred tons of lead was scavenged from the roofs and guttering which now would be worth about £1M. Parts of the palace and the church seem to have survived until the Civil War when they formed the frontline during various sieges. Today, we are left with a few walls of rubble core – all the facing stone gone.

So, amidst all of the destruction what became of Henry I’s body? The demolition gang were expecting treasure in the royal grave, possibly a silver-lined coffin, but they found nothing of value. Writing in the 17th century, herald and historian Francis Sandford tells us that Henry’s remains ‘were thrown out to make room for a stable for horses.’

Evidence of high-status burials around the east end of the church has been found over the centuries, albeit accidently. A body was discovered as far back as 1784 when the foundations for the original county gaol were being laid across the east of the monastic complex. The skeleton was contained in a lead coffin, complete and with a lower jaw full of teeth. Convinced they had found the king, the bones were ‘divided amongst the spectators’ and the coffin sold off to a plumber. However, it would seem that location of the discovery was well away from the site of the high altar and the skeleton was that of a man under thirty. Plus, Henry’s body was not in a great condition on interment and this state was probably worsened at the Church’s demolition during the search for possible treasure. So, these remains were too perfect, too young and in the wrong location.

In November 1815 some workmen were digging in the vicinity of the church’s east end looking for gravel to improve the path to the adjacent school. Less than three feet below the surface they came across what appeared to be the base of a stone sarcophagus. According to local vicar and amateur antiquarian Archdeacon Nares, the object was seven feet long and two and a half feet wide tapering to two feet. The sides were decorated with the feet of Romanesque style columns suggesting this was the bottom section of an elaborate early medieval tomb. It had been broken into two parts and there was no sign of an occupant.

Nares was convinced that with such sophisticated decoration it had to be a royal tomb and hence must be Henry’s. The damage was consistent with the supposed post-dissolution treatment of the tomb. The sarcophagus was kept in the school, but pupils and souvenir hunters gradually chipped away at the more decorative details. What was left was seemingly relocated to the ruined south transept of the church where it was placed in a wall under a mock canopy made from a rescued Tudor fireplace.

Chaos had followed Henry’s death in 1135. His sole legitimate male heir William Adelin had died in 1120 off Normandy in a shipwreck. The nobility would not accept being reigned over by his sister Matilda, widow of the Holy Roman Emperor, opting instead for her cousin Stephen of Blois. Matilda and her new husband Geoffrey Plantagenet did not recognise Stephen as king, plunging the country into a civil war lasting for 18 years. Peace was brokered when Stephen accepted Matilda and Geoffrey’s son Henry as his heir.

In the midst of this war known as the Anarchy, Stephen still had time to establish a monastery at Faversham in Kent. Like his uncle Henry before him, Stephen intended to be buried in the church also planned on a vast scale. It’s not known why he chose Faversham, but it was on a creek with good access to the Thames and Kent was an area under his control during the civil war.

Stephen, his queen Matilda, and son Eustace were all buried at Faversham. Royal patronage ended with his fledgling dynasty and the ambitious plans for the monastery were never fully realised. The church lost 100ft of its planned length of 360ft and the cloister was significantly reduced.

After its dissolution, the abbey’s materiel was shipped off to Calais, then an English possession, to reinforce its defences. What remained of Stephen and his family were apparently cast into the nearby creek with their lead coffins turned into musket balls. When archaeologist Brian Philp excavated the abbey in 1965, he located the royal tombs, and they were empty. There is a story though that the bones had been rescued from the creek and placed in Faversham parish church, the Victorians attributing an unmarked tomb to be their final resting place.

The Plantagenets took over in 1154 and ruled for the next 300 years. England was now part of an empire extending from the Pyrenees to Scotland which covered about half of France, thanks in part to the possessions of the formidable new Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine. The first Plantagenet king Henry II died in his native Anjou in 1189. He had requested to be buried at Grandmont Abbey in the Limousin, but the weather was too hot to take his body all that way so nearby Fontevraud Abbey became his resting place instead. Richard I followed a decade later, killed at a siege in western France. His lion heart however was mummified and sent to Rouen in Normandy and is now reduced to a brown powder.

Eleanor who outlived them both, commissioned a chapel where they could form a family group. She joined them in 1204 after a spell as an incumbent at Fontevraud in her widowhood. At least the warring family were united in death. None of their remains however survived the French Revolution, the chapel was destroyed, their bones scattered, and their effigies banished to a cellar. The Abbey became a prison which closed in the nineteen-sixties. Since then, it has been painstakingly restored with the Plantagenet effigies placed in the centre of the church albeit as cenotaphs.

Following the remarkable discovery of Richard III, there is an appetite to find other kings. Phillipa Langley who sponsored the search for the last Plantagenet is now looking for Henry I. Lacking Richard’s notoriety he has been dubbed ‘England’s forgotten king’. External factors have delayed her investigation which may result in another king being found in a car park – that of the former Reading Gaol.

What a fascinating article, but it makes me so sad to think about what was lost during the Reformation, Civil War and French Revolution.

‘Most of [Henry] was brought to Reading… and was laid to rest in front of the high altar’ – most of him?! What on earth happened to the rest of him? 🤣

LikeLike

Hi Nicola – Henry was embalmed at Rouen in Normandy. This involved removal of his innards which were interred at Notre Dame du Pre nearby – see Reading Museum site for more details.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This article was so interesting. I always appreciate the research and time these authors expend for us.

LikeLike

Susan, Was actually looking at Edward the Confessor recently as he is marked as related to us Pomeroy’s. I was looking for the reference used for. I believe Leonard POMEROY, where it says his relation to him.

Cheers Ken delapomeroy.com

LikeLike