Henry IV’s wife Mary de Bohun had died in 1394, before he became king. His motives for marrying Joan of Navarre, Duchess of Brittany, in 1403 are unclear. He may have believed he could have some influence on Joan’s son, John V, Duke of Brittany or perhaps he wanted to create a contrast between his marriage to a mature woman and his cousin, the deposed King Richard II’s choice to marry a seven-year-old French princess. Mary de Bohun had already given him plenty of sons so there was no pressure on Joan to have an heir.

Being the daughter of Charles II, King of Navarre and Joan of Valois, daughter of King John II of France made Joan an important member of the French royal family. She was probably born at Évreux in Normandy in 1368. As early as April 1369, there’s evidence the monastery of Santa Clara at Estella in Navarre received a florin a day for her upbringing. Her mother died when she was three. She did receive an education, and as a woman of the nobility, was taught etiquette and proper behavior, how to sew and dance, to play music and to run a household. By all accounts she was intelligent, charming and religious. Records indicate Joan and her sisters kept dogs and birds. As Queen, she had birds and would send them as gifts.

By 1369, Joan’s father had lost most of his territories in France, and Navarre had been invaded by the armies of Castile. Following the capture of twenty fortresses in the south of Navarre by the Castilians, King Charles made peace. The terms of the agreement forced King Charles to reside in Navarre with Joan remaining with her father to continue her education. In 1380, her father brokered a betrothal between Joan and Juan, the heir to the kingdom of Castile. However, the marriage never materialized.

King Charles sought allies and entered into negotiations with John de Montfort, Duke of Brittany. Brittany’s political situation was comparable to Navarre, being an independent state, owing fealty to the French crown. The Breton duke was also the 7th Earl of Richmond in England and owed allegiance to the English crown. Duke John had been married and widowed twice and had no surviving children. The alliance required papal dispensation, prolonging the negotiations.

Letters were finally drawn up in the spring of 1385, agreeing to the marriage. Preparations were made, the dowry raised, and the duke sent ships in the summer of 1386 to collect the bride. A proxy marriage took place in Bayonne Cathedral on September 2 and two days later, the ships sailed. The couple were married on September 11 in a small chapel at the manor of Saillé on the outskirts of Brittany.

A few months later, Joan’s father suffered a terrible accident. Due to an illness King Charles suffered, his physicians prescribed a treatment of wrapping him in linens doused in wine or spirits, with his bed warmed by hot coals. He had carried out the treatment several times but, on this occasion, the linens caught fire and burned the king up to his navel. He died in agony fifteen days later.

Joan gave birth to her first child, a son born on Christmas Eve, 1389, securing her position as Duchess. She gave birth to nine children in ten years. Joan provided advice to her husband and acted as intercessor in several particularly complex and problematic diplomatic situations. In October 1396, she attended the wedding of King Richard II of England and Isabella of Valois near Calais. It was a grand occasion and she may have met Henry Bolingbroke, the future King Henry IV, at the festivities. In April 1398, Joan and her husband traveled to England to attend the Order of the Garter Feast at Windsor Castle. Henry Bolingbroke had been forced into exile by Richard II in 1397, so he did not appear at the Feast. Henry may have met Joan during his exile in France or Brittany although there is no historical evidence of any actual meeting.

Joan’s husband died on November 1, 1399, leaving her as regent for her ten-year-old son. She performed her duties as regent admirably, restoring relations with some of her husband’s foes and resolving disputes. She ordered an impressive funeral for her husband and a magnificent coronation for her son. That same year, Henry Bolingbroke’s father, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster died and King Richard II denied Henry’s right to inherit all of his father’s patrimony. Henry proceeded to collaborate with other disaffected men in England and returned with a military force to depose his cousin. Parliament proclaimed him King Henry IV of England and he was crowned in Westminster Abbey on October 13, 1399.

Upon the death of Joan’s husband, Henry considered marrying her. Within three months, Joan sent ambassadors to England. Henry insisted on keeping the marriage secret but the presence of her ambassadors drew comments. Joan wrote him a letter on February 15, 1400:

“My most dear and honoured lord and cousin,

Forasmuch as I am eager to hear of your good estate – which may our Lord make as good as your noble heart can desire, and as good as I could wish for you – I pray you, my most dear and most honoured lord and cousin, that you would tell me often of the certainty of it, for the great comfort and gladness of my heart. For whenever I am able to hear a good account of you, my heart rejoices exceedingly. And if, of your courtesy, you would like to hear the same from over here – thank you – at the time of writing my children and I are all in good health (thanks be to God, and may He grant the same to you) as Joanna de Bavelen, who is bringing these letters to you, can explain more plainly…And if anything will please you that I am able to do over here, I pray you to let me know; and I will accomplish it with a very good heart according to my power. My most dear and honoured lord and cousin, I pray the Holy Ghost that He will have you in his keeping.

Written at Vannes, 15 February, the duchess of Brittany”

A papal dispensation was required for the marriage as they were related within the prohibited degrees of consanguinity, according to the Church. Joan received the papal bull on March 20 and her ambassadors arranged a proxy marriage ceremony at Eltham Palace on April 2, 1402. The speed of the marriage, as well as other considerations, surprised those surrounding the couple. Many in England remained unenthusiastic about the union and there was considerable opposition to it in Brittany and France.

Joan’s uncle, Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, intervened and visited Joan at Nantes in October 1402. He demanded she give up control of Brittany and leave all her children behind. She was compelled to surrender the regency to Philip, and relinquish custody of all of her children with the exception of her daughters Blanche and Margaret, who were five and ten. In the end, Joan was forced to give up her sons, her friends, her title and her home, which she must have found very difficult.

Henry had to explain why he was marrying a Frenchwoman at a time when England might go to war with France. These issues indicate it was not a marriage of convenience but most likely a love match, albeit with a political dimension. Along with the marriage of his daughters, Henry was seeking connections to ruling houses in order to achieve recognition of his newly installed dynasty. Henry spent Christmas 1402 at Windsor and made preparations to go to Southampton to meet his bride.

Joan left Nantes with her two daughters on December 26 and boarded ship on January 13. Rough weather forced the ships to land at Falmouth on January 19, 1403. With Joan heading west and Henry heading from the east, they met outside Exeter where the city entertained them with celebrations. From Exeter they made their way to Winchester Cathedral where the wedding took place on February 7, followed by a splendid feast. Joan was crowned in Westminster Abbey on February 26. The Earl of Warwick served as her champion. Henry took her to his favorite palace of Eltham and then they embarked on a tour of Kent.

Henry bestowed upon Joan her dower, a sum of ten thousand marks per annum. This was the largest dower of any English queen up to that point, making her one of the wealthiest people in the realm. In fact, it was so large, she had difficulty obtaining control of the manors on which it was assigned. Some of the properties were confiscated from rebels and later returned to their heirs. After a year, her dower was five thousand pounds in arrears and she began to assert her influence as queen consort.

Dozens of grants were made to Joan in order to collect what she was due. Some of these grants originated from the possessions of the late Queen Anne of Bohemia and Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster, the last wife of Henry’s father John of Gaunt. These properties included lands and income in Brighton, Odiham, Ipswich, Nottingham, Great Yarmouth, Bristol, Woodstock, Stafford, Havering atte Bower, the castle on the Isle of Wight and Leeds in Kent, among others.

On December 10, 1404, she was granted for life a tower at the entrance of the Great Gate of the Great Hall in the Palace of Westminster. The grant specified this tower would be used for council and business meetings, for the storage of her documents such as charters, and for the auditing of her accounts. This implies Joan meant to engage in exercising a substantial amount of fiscal self-determination.

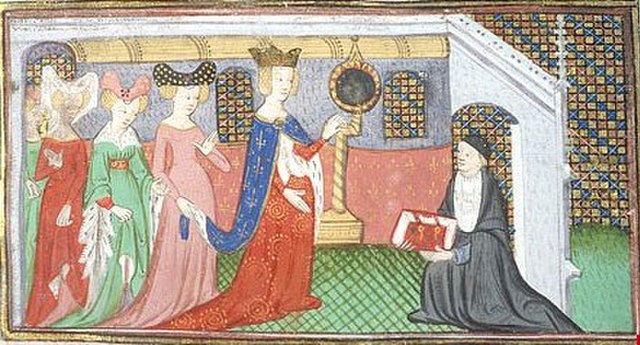

Henry was kept chronically short of funds throughout his reign and Parliament argued bitterly between 1404 and 1406 about the size and cost of the queen’s household, forcing her to dismiss most of her Breton servants, and keeping only a handful of essential persons. Joan certainly kept up with aristocratic fashion, ordering luxurious cloth for rich clothing. She enjoyed expensive foodstuffs, wine and spices and owned exotic animals. One of her superbly illuminated psalters still survives.

She intervened on behalf of poor and needy petitioners. There is no evidence of any complaints of her influencing the king or the government. If she did, it was done discreetly. She petitioned Henry to release Breton prisoners apprehended after a raid in Devon in 1405, and in July 1407, she contributed to the brokering of an Anglo-Breton truce with her son.

In 1406, those in power in Brittany compelled Joan to return Blanche and Margaret, separating her from all of her children. She actively pursued arranged marriages for her daughters. Joan was on good terms with her stepchildren in England, building long-lasting relationships with them. There is no evidence of any criticism of her behavior and those who came into contact with her in both her kingdoms admired her personally and in her public life.

Joan’s younger sons Arthur and Giles visited her in England several times and she continued to communicate with all her children in Brittany through written correspondence. In 1408, she commissioned a fine alabaster tomb in England and shipped it to Nantes Cathedral where it was installed over her first husband’s grave. She also ordered a splendidly bejeweled reliquary in London as a present for her son, Duke John V. It is now in the Louvre Museum in Paris. In 1411-12, Joan urged the English to not enmesh themselves in the ongoing complex Armagnac-Burgundy feud in France.

Shortly after her marriage, Henry began to suffer from acute attacks of a mysterious illness. Going forward, he declined slowly. In the summer of 1408, he had a violent seizure, causing him to lose consciousness, and no one was sure if he would live. This happened again in 1409 and even he believed he would die, as he drew up his will, in which he requested Joan be endowed with the Duchy of Lancaster.

He would recover and this state of affairs lasted for several years. Henry would be at death’s door only to improve. Henry’s movement was limited for the rest of his life and he rarely ventured far from London. Parliament attempted to curtail his powers and he increasingly relied on his eldest son, his council and Joan. Henry spent his last Christmas with his wife at Eltham. Joan and his sons Henry and Humphrey were with him when he died on March 20, 1413.

King Henry loved both his wives dearly and was indulgent, loyal and faithful. He chose to be buried with Joan and she commissioned the tomb she would eventually share with him in Canterbury Cathedral. Joan was a widow at forty-three, on good terms with her many children and stepchildren and played no significant role in the politics of the realm after her husband’s death. She maintained a good income and some of her Breton entourage had married English men and women. It makes sense she would remain in England rather than return to Brittany. The first few years of her retirement went quietly by.

It was Henry V’s intention to honor his father’s provisions for Joan but he had grand ambitions. He would revive the Plantagenet claim to the French throne. He argued his rights had been denied through a series of truces and alliances since the death of King Edward III, and he was attempting to bring peace after thirty years of failed diplomacy. It was his belief the French had betrayed the 1360 Treaty of Brétigny by encroaching on English sovereignty in Aquitaine.

In the summer of 1415, Henry invaded France and won the Battle of Agincourt. During the fight, Joan’s son Arthur was taken prisoner and her son-in-law, Marie’s husband Jean d’Alençon, was killed. Despite these tragedies, Joan participated in Henry V’s grand victory procession through London in November. Henry remained determined to continue the fight in France and he needed Joan’s income to finance the war and create a new dower for his intended bride. After Agincourt, Parliament forced Joan to expel some of her Breton servants. Despite the English harboring hostility against Brittany, they were not attacking the Dowager Queen personally and appeared to maintain great respect for her based on her conduct as queen consort.

During August 1419, the possessions of Joan’s personal confessor, Friar John Randolph, were seized. From the description of the of appropriated goods, it is clear they belonged to Joan. No reason for the seizure is given but by September, it was reported Randolph had accused Joan of plotting and scheming for the death and destruction of Henry V. Another two members of her household were also incriminated.

It is unclear if this cunning plan was Henry V’s idea or someone in his council. They arrested Joan with all her lands and income reverting to the Crown. Accused of witchcraft, she never went to trial. It was the perfect state of affairs to take her fortune. If she were put on trial and found guilty, they would have executed her. The king had the ability to commute the sentence but she would have been under suspicion for the remainder of her life, something she could never recover from. If she were found innocent, they would have been compelled to return all her lands, income and property. Left in this limbo state, Henry could keep the income for the Crown.

Despite the fact Joan was kept in captivity, she lived in relative luxury with some limited freedoms. She began her imprisonment at Rotherhithe and they later moved her to Leeds Castle and to Pevensey. She maintained several servants and was allowed to have visitors, including her stepson, Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester. While payments for her expenses were later reduced, she didn’t live in poverty and received financial help from some of her friends.

In 1420, King Henry negotiated the Treaty of Troy with the French, which included his marriage to Charles VI’s daughter, Catherine de Valois. With the war ended, Joan could rightfully expect to be released. While the payments for her expenditures were increased, the English treasury could not afford to pay for two queens. So, her captivity continued. Catherine of Valois established her position as Queen with the birth of a son, the future King Henry VI.

Henry returned to France. During the fighting, he contracted dysentery and knew he was dying. On July 12, 1422, Henry ordered Joan be released and the gradual restoration of her position, personal goods, and income from some of her more modest properties. These properties were administered by faithful servants, some of whom were confirmed in office by King Henry VI. By now she was spending most of her time in the palace of King’s Langley in Hertfordshire. A major portion of this palace burned down on March 25, 1431, due to the carelessness of a minstrel, and she then resided in her manor at Havering atte Bower in Essex.

The young king never visited his step-grandmother but he did become great friends with his cousin, Joan’s grandson Giles, who visited England from 1432 to 1434. The Earl of Warwick, who championed Joan at her coronation, was still in her service and presumably updated her on the life of the king. She lived comfortably and quietly in retirement, visiting religious institutions and enjoying visits from family and friends. She died sometime in July 1437 at the age of sixty-seven at Havering. During the funeral, organized by the Duke of Gloucester and the council, she was buried with all honors next to her husband in Canterbury Cathedral on August 11. Her effigy was added later to the tomb she had commissioned for King Henry. There is no written historical evidence Joan ever participated in any form of witchcraft.

Further reading: “The Fears of Henry IV: The Life of England’s Self-Made King” by Ian Mortimer, “Royal Witches: From Joan of Navarre to Elizabeth Woodville” by Gemma Hollman, “Queens Consort: England’s Medieval Queens from Eleanor of Aquitaine to Elizabeth of York” by Lisa Hilton, “The Last Medieval Queens” by J.L. Laynesmith, Henry IV [known as Henry Bolingbroke] entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National biography written by A.L. Brown and Henry Summerson, “The Reign of Henry VI” by R.A. Griffiths

Reblogged this on History's Untold Treasures and commented:

H/T The Freelance History Writer

LikeLike

[…] early modern period, there were only five queens from the Iberian Peninsula: Berengaria of Navarre, Joan of Navarre, Katherine of Aragon, Catherine of Braganza and Eleanor. Most wives of English kings came from […]

LikeLike

At least, she did not have the pressure to have a son and heir for Henry the Fourth. There’s must have been a truly happy union. Joan did have a long and complicated history and it was sad that she had to give her sons but at least had her daughters.

LikeLike