“My son, my friend, if Fortune does me the wrong of taking him [her husband] from me, I will do with the honest people that I have here the best that I can, and you shall be advised of everything. For, my friend, after God, I can have no hope and consolation save in you and my other children. I cannot be without grief so great that in truth I have as much as I can bear of it. Your good mother, Anthoinette” – letter from Antoinette, Duchess de Guise to her son François

Claude of Lorraine, Duc de Guise lay dying with his wife Antoinette at his bedside. He received the Catholic last rites, and stated “If it please God, I am departing to go and join the saints”. He died on April 12, 1550, at his home in Joinville.

They decided to postpone the funeral until absent members of the family could arrive to take part. The body of the duke was embalmed and deposited in the Church of Saint-Laurent, in a chapel draped with black velvet, decorated with the coats-of-arms of the various royal houses from which he claimed descent. A month after the death of Claude, his brother Cardinal Jean de Lorraine, returned from Rome where he had participated in the Conclave necessitated by the death of Pope Paul III. As the Cardinal arrived in Lyon, they informed him of his brother’s death. He seemed greatly affected and a few days later, while at supper at Nogent-Sur-Vernisson, he had an attack of apoplexy and died that night.

The Cardinal’s remains were brought to the Church of Saint-Laurent by the Cardinal de Guise and the Bishop of Albi and placed beside his brother. After lying in state for forty days, the remains of the cardinal were buried in the Franciscan convent of Nancy. The remains of the duke were removed to the convent of Notre Dame de Pitié which he had founded, where they were deposited on an immense state bed in the principal guest chamber, to await interment.

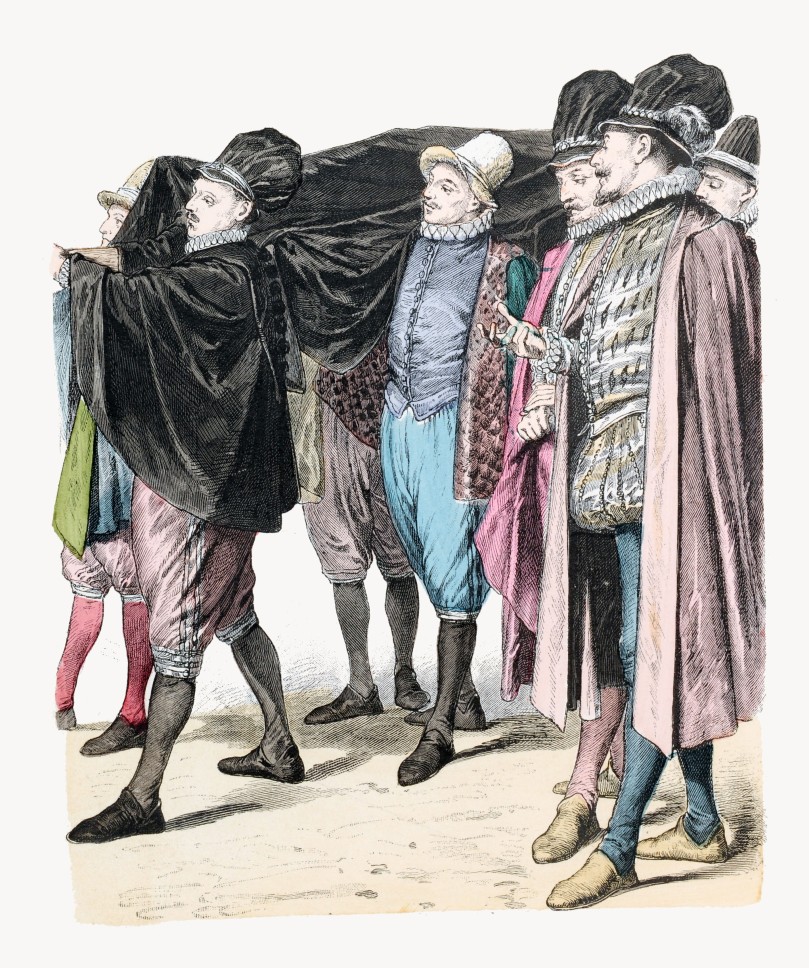

On July 1, the family gathered together for the obsequies, which had been authorized by King Henri II of France. Twelve criers headed the procession from the convent to the château, sounding their hand-bells and calling out at intervals: “Monseigneur le duc de Guise is dead; pray God for his soul!” Then came a hundred poor men clothed in black, each carrying a lighted taper in his hand, followed by a similar number dressed in white; the clergy of Joinville and the neighborhood; the high bailiff of Joinville and the officers of justice; the deputies from the Estates of Burgundy; the officials of the deceased prince’s household, the lackeys walking with their hands crossed on their breasts indicating their master no longer needed their services; an equerry leading Guise’s great war-horse, “barded for battle” [covered in various pieces of defensive armor for a horse].

Following the horse were seven gentlemen bearing the duke’s spurs, gauntlets, lance, and so forth; the banner of Lorraine, followed by the eight banners of the “lines paternal” and “lines maternal”; the pennant of the House of Guise; the duke’s company of men-at-arms; the King-at-Arms of Lorraine, Edmond du Boullay; the duke’s chief equerry, leading his cheval d’honneur – the horse he rode on state occasions- it’s magnificent trappings supported by four lackeys; the King-at-Arms of France, and twenty gentlemen bearing on their shoulders the great state bed, upon which lay the effigy of the duke, and beneath it his coffin, the pall of which was supported by four knights of the Order of Saint-Michel. Finally came the princes and great nobles or their representatives, the most conspicuous being the Comte de Brienne, of the House of Luxembourg, a relative of the widowed Duchess de Guise, who, as a particular mark of his affection, had brought with him twenty-five poor men, dressed in mourning at his own expense.

After the funeral service, which was performed by the Cardinal de Givry, the body was laid to rest in a chapel of the church of Saint-Laurent, known at the time as the “Holy Chapel” from the number of relics it contained, but later known as the “Chapel of the Princes”, on account of its tombs. Then the King-at-Arms of Lorraine stepped forward and cried “Silence! Silence! Silence! The very illustrious Prince Claude de Lorraine, Duc de Guise, and d’Aumale, Marquis de Mayenne, Baron de Joinville, etc., etc., is dead…Claude de Lorraine, Duc de Guise, peer of France, is dead….Monseigneur le Duc de Guise is dead, and his ecclesiastical ceremonies are finished. Pray God for his soul!”

Then, turning towards the new Duc de Guise, he continued: “Long live the very high, very puissant, and very illustrious François de Lorraine, Duc de Guise, peer of France, etc., etc., eldest son and principal heir of the very illustrious prince of immortal memory, today buried. Long live Monseigneur le duc François!”

The last ceremony of all took place in the great dining hall of the château (the Salle des États), after the chief mourners had dined, when Marinville, captain of the Château of Montéclair and maître d’hôtel to the late duke, solemnly broke his baton of office in two, casting the pieces into the middle of the hall, symbolizing the breaking up of his master’s household, while the King-at-Arms cried: “The very high and very illustrious Prince Claude de Lorraine, Duc de Guise, is dead and his household is dispersed. Let each one provide for himself.” In reality, none of the duke’s servants had to provide for themselves. The more elderly received handsome pensions and the others were taken into the service of the new duke or one of his brothers.

The widowed duchess subsequently erected for her husband and for herself a mausoleum in black and white marble, jasper, alabaster and porphyry, one of the most magnificent tombs of France, ornamented with a number of beautiful sculptures, representing the battles, skirmishes, and captures of towns in which the late duke had taken part. Above the tomb were their statues, recumbent, and within the chapel four marbles statures representing the four virtues, each of which supported a stone cornice on which were statues in white marble of Claude of Lorraine and Antoinette de Bourbon, each clothed with the ducal mantle, kneeling in prayer.

On the monument was an engraved Latin epitaph:

“To the memory of Claude de Lorraine, very wealthy prince, having acquired the name of the father of the country, for the signal victory which he gained over the heretical enemies at Saverne, town of Alsace, and for having preserved the inhabitants of Burgundy and Flanders, who died prematurely, to great grief and sorrow of all.”

Further reading: “The Brood of False Lorraine: The History of the Ducs de Guise (1496-1588), Volume 1″ by H. Noel Williams (1910)

another very interesting piece

LikeLiked by 1 person