We are happy to welcome to the blog Dr. Katrin Kania who joins us with a guest post about medieval spinning. She is a freelance textile archaeologist and teacher as well as a published academic who writes in both German and English. She specializes in reconstructing historical garments and offering tools, materials and instructions for historical textile techniques. Find her website at http://www.pallia.net and her blog at togs-from-bogs.blogspot.com. She also tweets under @katrinkania.

Dr. Kania and Dr. Gillian Pollack have written a new book which is being released in the United States this week called The Middle Ages Unlocked: A Guide to Life in Medieval England, 1050-1300. The book is available from Amberly Publishing.

I’m a textile archaeologist, and one of the topics I have focussed on in recent years is spinning. Spinning – turning fibres into yarn – is basically a very simple process. Especially in the Middle Ages, when the only tool available to do the spinning was the humble hand spindle. This tool is a stick tapering towards both ends and a spindle whorl which serves as a weight and provides better rotational properties to the spindle as a whole.

On medieval illustrations, spindles inevitably are shown together with a distaff. That’s another stick, this time for holding the fibre supply. Spindle and distaff together are used to make yarn, which in turn is used for all kinds of different textile techniques, foremost of them weaving. Textiles were an important part of daily life, and clothes as well as textile furnishings were used to show one’s wealth and status. Textiles were also one of the most important goods for trading.

So far, this all seems straightforward, right? However, there are many puzzling questions attached to textile works and spinning. For instance, while we have pictures of men combing wool and weaving, we have virtually no pictures of men spinning. Does this mean that only women did the spinning?

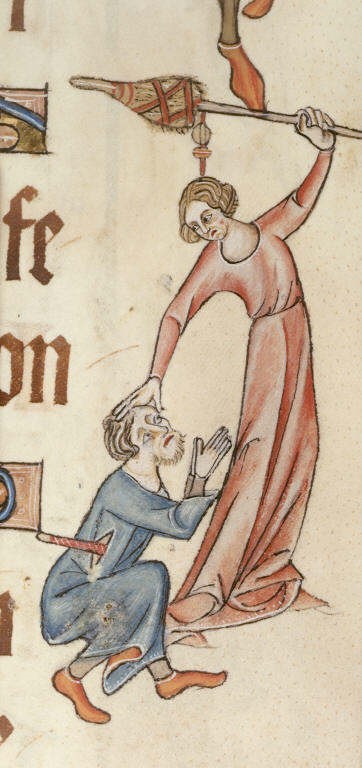

Both pictures and texts seem to firmly put spinning into the female camp, but this might be due to a Bible passage. In Proverbs 31:19, it says in praise of the good wife “She puts her hands to the distaff, and her hands hold the spindle.” (English Standard Version). Women might thus be shown spinning to demonstrate their productiveness, their integration into society, their positive wifely qualities. This is turned on its head when women use just these indicators of their conformity to beat up their husbands, like the lady in the picture above from a 14th century manuscript does.

So far, so good. But let us look at the work force necessary to do all the spinning. Modern people often underestimate the quality of medieval textiles. Fine, evenly woven fabrics were appreciated and sought after in medieval times. While we do have some examples of coarse, rough weaves with uneven yarns, this was not the norm – quite the opposite.

Let’s look at a medium-quality wool fabric, done in a simple weave, with about 15 threads per centimeter in both warp and weft. (Warp are the threads the loom is dressed with, weft are the threads the weaver inserts.) That means a square centimetre of our fabric contains 15+15=30 cm length of thread. Let’s say, for ease of fiddling with numbers, that our fabric is one metre wide. To weave the length of one centimetre, we need 100x our 30 cm – that is 3000 cm, or 30 metres. For one metre of fabric, that means we need 30 metres times 100 – 3000 metres. Three kilometres of yarn for just one square metre of fabric!

To put this into context, you’d need approximately 3-5 metres of this fabric to make a woman’s dress, depending on the size, fit, and cut. So we are talking about serious yarn production here, kilometres and kilometres. Which means a lot of time must have been spent spinning. How much exactly?

Well, that’s the next vexing question. We can try to reconstruct the spinning style used in the Middle Ages, and we can try to do measurements of how fast a spinner today is. There’s also data about spinning speeds published in several books, but they are sometimes extrapolations from the maximum achievable speed of rotation, and vastly over a humanly possible speed. Which means we actually don’t know how fast spinning went, in general, in the Middle Ages.

My own tests and evaluations have resulted in my own personal estimate of a speed of about 40-100 metres per hour, depending on the spinner, the quality of the fibre preparation, and the quality and thickness of the yarn being made. Some of the numbers out there are much higher, but even if you estimate a yarn production speed of, say, 200 metres per hour, you’d still need to spend about 45 hours spinning to make enough yarn for three metres of our imaginary fabric. (A little more, actually, since you lose a bit of yarn at the start and the end of the fabric, and there’s shrinkage when you take it off the loom, so you could add about 10% as a rough guesstimate.)

Spinning thus needs a lot of time. Spinning, as opposed to weaving fabric, can be done almost anywhere, and can be done in between other tasks. It can be done on the go, distaff tucked under your arm or into your belt. It’s also relatively easy to do as long as your expectations are not too high – as always with crafts, the higher quality you want, the more skill it takes.

Limiting spinning work to the female part of the population would mean losing a lot of possible workforce for spinning. Peddlers could well have been spinning while travelling. Herders looking after their animals may well have spent time spinning. So many others could have spun – but of course, if spinning was associated with femininity, this would not have been something talked about or shown a lot.

So is the spinning = woman’s work true, or not? We can’t really tell. Such a simple task, so many unsolved questions…

Further reading:

General information about historical textiles:

Wild, John Peter. “Textiles in Archaeology” by John Peter Wild, Shire Publications, 2003

“A History of Textile Art” by Agnes Geijer, Leeds: Sotheby Parke Bernet/Pasold Research Fund, 1982.

Archaeological finds related to textile production:

Article by Penelope Walton Rogers, “Textile Production at 16-22 Coppergate”, The Archaeology of York Vol. 17: The Small Finds. York: Council for British Archaeology, 1997.

Spindles as symbols:

“Equally in God’s Image: Women in the Middle Ages” by Julia Bolton Holloway, Constance S. Wright and Joan Bechtold. New York [u.a.]: Lang, 1990

Article by Alison Stewart, “Distaffs and Spindles: Sexual Misbehaviour in Sebald Beham’s Spinning Bee”, Faculty Publications and Creative Activity, Department of Art and Art History (2003): 4.

Dr Gillian Polack is a novelist, editor and medieval historian as well as a lecturer. She has been published in both the academic world and the world of historical fiction. Her most recent novels include “Langue[dot]doc 1305” and “The Time of the Ghosts” (both by Satalyte publishing). Find her webpage at http://www.gillianpolack.com and her tweets under @GillianPolack.

[…] We are happy to welcome to the blog Dr. Katrin Kania who joins us with a guest post about medieval spinning. She is a freelance textile archaeologist and teacher as well as a published academic who writes in both German and English. She specializes in reconstructing historical garments and offering tools, materials and instructions for… […]

LikeLike

‘there are divers men who are worsted spinsters’.

J. H. Baker, ‘Male and Married Spinsters’, The American Journal of Legal History, 21 (1977), p. 256.

This came from a trial in 1540. The speaker was J. Spelman.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] I may have to finally go get a real distaff. (On a more serious note, that image is featured in an article by Katrin Kania published at The Freelance History Writer. Ms. Kania is a textile archaeologist who specializes in […]

LikeLike

I spin and weave, and am always interested to find out a bit more about these crafts and activities. I enjoyed your post very much. My husband has read a lot on Medieval history, and we were discussing the conundrum of who had the time to spin such large amounts of yarn. He suggested the children, as it appears that ‘childhood’ as we understand it is a relatively new concept, and that young people were expected to work and contribute to the community from a much earlier age.

LikeLike

I believe your husband could be right Sharon. It is entirely possible the whole family was involved.

LikeLike

[…] For The Freelance History Writer Katrin wrote about spinning […]

LikeLike

I have been a weaver for many years, but never a spinner. I enjoyed your article. The timing was apt because I am preparing an Art Talk for the Tucson Museum of Art which includes a brief history of weaving. Perhaps I should include something about the spinning too. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m a spinner, weaver and admirer of the Middle Ages so this post was very interesting for me. Thanks for writing it. I especially enjoyed the picture of the woman about to hit the man with her spindle and distaff. Such useful tools!

LikeLike