Sebastião Jose de Carvalho e Mello, better known after September 1770 as the Marquess of Pombal, is a controversial figure in Portugal for many reasons. He served as ambassador to London and Vienna under King João V where he was exposed to the ideas of the Enlightenment and the advancements in science at the Royal Society in England. Portugal had not had much experience in these intellectual pursuits so when Pombal was recalled to Portugal in 1749 and given the post of secretary of state for foreign affairs and war by King João, he was uniquely qualified to convey these ideas to the country. Despite having no administrative experience, his appointment was ratified on August 3, 1750 by King José who had succeeded King João. Pombal would have great influence in the government of Portugal from 1750 until 1777.

Pombal’s reputation and standing was greatly enhanced with King José when he demonstrated his absolute command of the reconstruction of Lisbon after the Great Earthquake on November 1, 1755. Essentially serving as prime minister and having the king’s full support, Pombal proceeded to reorganize Portuguese education, finance, the army and the navy. He created new industries and trade monopolies and promoted the development of Brazil and Macao. At the same time he enhanced autocracy and regalism and advanced the secularization of Portugal.

Less than two years after the Earthquake, King José gave Pombal increasingly dictatorial powers. In this process, Pombal made many enemies and bitter disputes between him and the nobility and amongst the nobility themselves became more frequent. In 1756, there was a failed attempt by the nobility to persuade King José to dismiss Pombal. As tensions increased, a frightening incident occurred on September 3, 1758.

On that night, around eleven o’clock, King José was returning to Ajuda Palace by chaise after visiting his mistress, Teresa de Távora, the wife of the first son of the old marquis of Távora, one of the country’s most illustrious grandees. With the king in the chaise were his retainer Pedro Teixeira and a coachman, Custódio da Costa. The coach was attacked in a narrow alley by men on horseback. Shots were fired and the coachman was injured. King José was wounded by two shots, one in the arm and one in the thigh. Somehow the coachman managed to speed away from the scene and make his way to the home of the king’s surgeon which was nearby and where the king received medical care for his wounds.

At first, little was publicly stated about the incident. The official story was that the king had been incapacitated by a fall and the queen was made regent on September 7. But almost immediately, rumors were spreading that an assassination attempt had been made on the king’s life. In the meantime, Pombal’s agents were intensely gathering evidence and suspicion predictably fell on the Távora family.

Finally on December 9, Pombal announced the formation of an investigative tribunal which included himself and other secretaries of the government. A detailed account of the attack was issued which confirmed some of the rumors. Money, crown offices and preferment were promised to those who were willing to testify against those involved in the attack. Arrests swiftly followed.

Those taken into custody included: the duke of Aveiro, his sixteen-year-old son the marquis of Gouveia, the marquis and marchioness of Távora, their two sons, Teresa de Távora, the marquis of Alorna and the counts of Atougeia, Óbidos, Vila Nova and Ribeira Grande. All of those arrested were closely associated by bonds of blood and marriage. Also taken into custody were about a dozen Jesuits, one of them being the confessor of the marchioness of Távora. In addition, the tribunal ordered some of the attendants or servants of the accused grandees be detained.

From December 15, 1758 until January 8, 1759, interrogations were held with torture used on sixteen of the prisoners. With little or no opportunity to defend themselves, verdicts were pronounced on January 12 with sixty individuals being convicted. Most of the sixty, including the marquis of Alorna, the counts of Ribeira Grande, Óbidos and Gouveia, four brothers of the marquis of Távora and nine Jesuits were sentenced to indefinite imprisonment. However, six grandees and five commoners were sentenced to death.

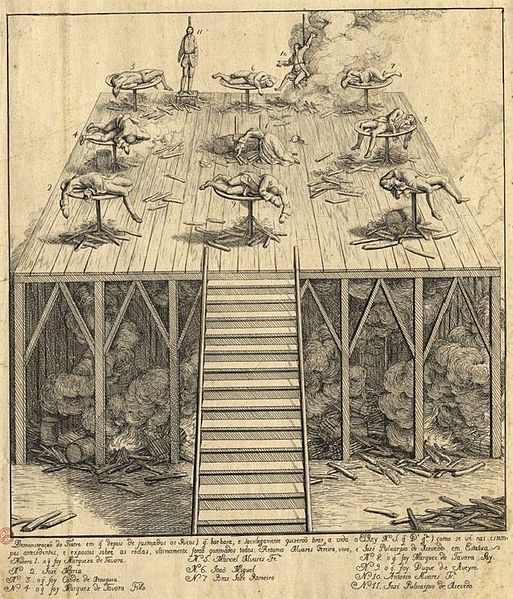

The executions took place the next day before a huge crowd. Using gruesome techniques including wheels, hammers and broken bones and strangling, the duke of Aveiro and the marquis of Távora, Távora’s two sons and the count of Atougeia and the commoners were killed. The marchioness of Távora was beheaded and the retainer of the duke who had actually fired the shots was burned alive. All these proceedings took up most of the day. When all was over, the scaffold with the remains of the victims was set alight and the ashes were discarded in the Tagus River.

Many questions still remain and are debated to this day by historians. Was this a genuine attempt to kill the king? If so what was the motive? Who knew about the plot? There were rumors that the real victim was Pedro Teixeira who had a disagreement with the duke of Aveiro. But the preponderance of the evidence appears to show an attempt was made on the king’s life and possibly as many as two hundred and fifty people knew about the plot ahead of time.

The duke of Aveiro at first protested his innocence in the matter but later confessed he had paid three of his servants to fire the shots. This admission was obtained under torture and may therefore be tainted but other prisoners confirmed Aveiro’s role in the matter. Aveiro held a grudge against the king’s government for cutting off some of his income and for halting his son’s proposed marriage to the daughter of the duke of Cadaval.

An attempt on the life of the monarch was serious business and it was standard practice to execute the perpetrator. And there were political demands that necessitated the salutary example of punishment. However, the brutality of punishing the nobility in public on the wheel was clearly not in the European tradition. And the gruesome spectacle aroused strong emotions in Portugal as well as the outside world. This form of execution had never been seen in Portugal before. In the past, nobles such as the duke of Braganza, the marquis of Vila Real and the duke of Caminha had been beheaded.

While it is known that Pombal wanted to teach the grandees a lesson, he was not solely responsible for the sadistic nature of the executions. King José and Queen Mariana Vitória were resolved to have the perpetrators punished with the utmost severity. In these cases, the royal will was paramount. It also wasn’t Pombal’s plan to destroy the aristocracy as an institution. He still believed in social hierarchy but he did exclude them from central decision-making, lowered payments to the grandees and kept their total number stable.

With this case, the nobility had been frightened into submission. Pombal went one step further. He alleged that the Society of Jesus was acting as an autonomous power within the Portuguese state and that its international connections were an obstacle to the strengthening of royal power. He therefore expelled the Jesuits from Portugal and from the colonies and confiscated their property, adding it to the crown. He became the leading opponent of the Jesuits in Europe. He also took this opportunity to weaken the grip of the Inquisition in Portugal.

A judicial review of the Távora case made twenty-three years later verified the guilty verdicts only for the duke of Aveiro and three of his servants. There were countless people who were imprisoned over the affair with no trial and no release date. King José was succeeded by his daughter Queen Maria I. She forced Pombal from office immediately and released eight hundred Pombaline prisoners as requested by King José on his deathbed. Among these were a handful of gaunt survivors of the Távora trial. The judicial review concluded the Távora family had been condemned unjustly. The family was exonerated and their name and rights were restored but their titles and properties were not because they had been passed on to others.

Further reading: “A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire: Volume One” by A.R. Disney, Dutra, Francis A. “The Wounding of King José I: Accident or Assassination Attempt?” Mediterranean Studies, vol. 7, 1998, pp. 221–229. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41166871

Reblogged this on Anniegoose's Blog.

LikeLike

Absolute power corrupts absolutely. Fits this horrific recounting to a “T”.

Bravo Queen Maria I!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Janet's Thread 2.

LikeLike