A grand-daughter of Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, Margaret was destined to be a pawn for her family’s political fortunes. Her life was comprised of many twists and turns. She would become a consummate negotiator and assist in bringing reconciliation between her family and the King of France. For this role, she received high praise from her second husband’s biographer.

Margaret, born c. 1393, was the eldest daughter of John the Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria. At the time of her birth, her father was Count of Nevers and heir apparent to his father Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. Margaret had five sisters and one brother Philip and grew up in a loving family. She was given an education worthy of her rank and lived in various Burgundian palaces such as Rouvres and Montbard. She was very close to her paternal grandmother, Margaret, Countess of Flanders who lived in Artois.

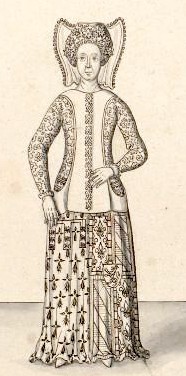

The chroniclers were not very complimentary about the looks of Margaret and her sisters. Whether this was for political reasons or the girls didn’t meet the standards of beauty for the time is not clear. At the time of Margaret’s birth, there was civil war in France between the cousins of the house of Burgundy and the house of Orléans who were known as the Armagnacs. King Henry V of England took advantage of this chaos to pursue his alleged claim to the throne of France. All of this strife would have an impact on the life of Margaret.

Her grandfather Philip the Bold had formulated a plan. He would indefatigably pursue advantageous marriages for his children and grandchildren with the children of his nephew King Charles VI of France. This plan included Margaret’s marriage to the king’s eldest son, the Dauphin. Margaret’s brother Philip was to marry Charles VI’s daughter Michelle. Margaret was engaged to the Dauphin Charles in January 1396 and after this she was known as the madam le Dauphine. Unfortunately, the Dauphin Charles died in early 1401.

On April 28, 1403, a document was drawn up and signed by King Charles VI regarding Margaret’s marriage to the new Dauphin Louis, Duke of Guyenne. This document gave his word as king that a marriage contract would be drawn up as soon as possible as required by Philip the Bold and Margaret’s father John the Fearless. The king also promised Queen Isabeau would consent to the agreement. There are no witnesses to this document so Philip the Bold must have gained the King’s consent in a private moment. Charles VI suffered from mental illness and the nobles around him were prone to making agreements with him when he not in complete control of all his faculties.

This agreement was a great political triumph for Philip the Bold and this particular marriage would bolster Philip’s influence over the king. His greatest hope was that a member of his family would become Queen of France. He also hoped to counterbalance the influence of the king’s brother Louis of Orléans. This agreement put an end to Louis’ plan to marry the Dauphin into his own family. Louis of Orléans obtained an ordinance from the king two days later voiding the marriage agreement for Margaret and Louis. But a few days later, the king rescinded the document. However, Louis did not give up in his efforts to annul the marriage before it was consummated.

Margaret’s dowry consisted of the castles and castellanies of Isle, Villemaur and Chaource, all of which were located in Champagne. These properties provided a yearly income of three thousand livres tournois. She was to be given two hundred thousand francs to purchase property for Louis, herself and any children they had but there is no record of this ever being paid. If there were no children, the dowry was to revert back to Margaret. An application for papal dispensation was made due to the bride and groom being second cousins. The couple were officially affianced in the king’s presence at his request before the dispensation arrived.

The marriage was celebrated on August 30, 1404 in Paris. Margaret lived at the French court until the marriage was consummated. She was under the guardianship of her husband’s mother Queen Isabeau, who oversaw her education and daily life. Shortly after her marriage, Margaret’s grandfather died and her father became Duke of Burgundy.

It was at this time the Italian-French author Christine de Pizan wrote an educational manual called “The Treasure of the City of Ladies”, also known as “The Book of the Three Virtues” and dedicated it to Margaret. Her father may have commissioned the work as a substantial payment was made to Pizan after the book was presented. The manual was meant to prepare Margaret for her duties first as Duchess of Guyenne and later as Queen of France.

The struggle between the Burgundians and the Armagnacs intensified when Margaret’s father became Duke of Burgundy. In August of 1405, Louis of Orléans had gained ascendancy in the French government after forming an alliance with Queen Isabeau. John the Fearless was concerned there was a conspiracy to annul Margaret’s marriage and took an opportunity to, for all intents and purposes, kidnap Margaret’s husband. Margaret had been taken to Melun with the royal family in a hasty escape before the Dauphin was seized.

The Dauphin was eventually released but John the Fearless was complicit in the murder of the Duke of Orléans in November of 1407. He relied on Margaret’s association with the royal family to shield and protect him from prosecution for the murder. Margaret and Louis consummated their marriage in 1409. On November 7, 1412, Margaret and Louis attended a grand banquet and dance at her father’s Hôtel d’Artois in Paris.

Open civil war broke out in the spring of 1413. Both the Burgundians and Armagnacs wanted control of the government and this included control of the Dauphin who was acting as regent during his father’s bouts of mental illness. Margaret’s father incited the butchers of Paris, called the Cabochiens (after their leader Simon Caboche), into revolt. The rebels wanted to purge the Dauphin and Dauphine’s household. On April 28, the Dauphin’s house was broken into and one of Louis’ servants was torn from the arms of Margaret as she tried to protect him. Several ladies and damsels of her household were arrested and imprisoned. This must have been pretty frightening for Margaret.

Margaret was to pay a high price for her father’s role in the Cabochien Revolt. In an angry response, Louis banished her from court and sent her to the castle of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. He took a mistress named Girarde Cassinel. She was the daughter of Guillaume Cassinel, lord of Pomponne and Romainville and served as cupbearer and later chamberlain in the king’s household. Her family had strong ties to the Orléans-Armagnac allies.

Margaret’s father fell from royal favor and in 1415, he sent ambassadors to court asking that the banishments of his followers be revoked. He also pleaded that his daughter be returned to the side of the Dauphin. Louis never did reconcile with Margaret and he eventually sent her to Marcoussis where she lived until he died.

In early December of 1415, Louis became ill, probably of dysentery. On December 27, ambassadors of John the Fearless arrived in Paris to forward several requests regarding his daughter. The Duke asked that Margaret be allowed to come to the dying Dauphin’s side and for guarantees that her widow’s dower be given to her and that one half of the Dauphin’s movable goods be assigned to her as was customary. The ambassadors were told that Margaret was fee to go but her dower could not be discussed due to the illness of the king. Louis died on December 28 and at that point, they were told the Dauphin’s movables belonged to the king.

Margaret arrived in Lagny-sur-Marne on January 9 and on the 10th she departed for Burgundy. She never received her widow’s dower while King Charles VI was alive. All of Louis’ movables were sold to pay the king’s expenses in January 1416. Margaret lived in Burgundy with her mother and two of her sisters, dependent on the court of her father.

In September of 1419, Margaret’s father was assassinated with the complicit participation of her brother-in-law, the future King Charles VII. Her brother Philip was now Duke of Burgundy and she was under his care. As early as 1422, Philip was planning on marrying Margaret to a new husband along with making an alliance with the English king. The Triple Alliance or Treaty of Amiens was signed on April 17, 1423. The signatories were Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy, John, Duke of Bedford and John V, Duke of Brittany. The treaty provided for two marriages: Margaret to Arthur, Count of Richemont who was the brother of John V of Brittany, and Margaret’s sister Anne was to marry John, Duke of Bedford who was acting as the regent for the King of England in France.

Arthur was an intimate friend of Margaret’s first husband the Dauphin so she knew him from her time at the French court. She was not amused at the thought of marrying a man she considered of lower rank than herself. She complained to her brother that Arthur had an unpaid ransom to the English who had taken him prisoner after the Battle of Agincourt. All of her sisters had married Dukes. She had been the Dauphine of France and Duchess of Guyenne. How could she marry a mere count?

Philip dispatched his trusted councilor Renier Pot to persuade Margaret. Pot was emphatic that her brother needed to confirm his alliance with Brittany and Arthur had the titular title of Duke of Touraine. He told her Arthur was a valiant knight, renowned for his loyalty, prudence and prowess, well-loved and likely to come into possession of much influence and authority in France. Pot reiterated that Margaret was still young, had been a widow for a long time and needed to have children, especially since Philip had no legitimate children of his own yet.

Margaret capitulated to these arguments and she and Arthur were married at Dijon on October 10, 1423. Almost immediately, Arthur became a dominant member of the French court. He would be a good friend and pro-Burgundian supporter of his brother-in-law in French political affairs. Margaret would become a loyal and devoted wife. Arthur became Constable of France in the service of King Charles VII in 1425. Margaret managed his estates in Parthenay when he was away at court or fighting on the battlefield against the English.

She protected her brother when he fell out of favor with King Charles VII, acting as mediator in negotiations to reconcile him with the king. When Charles VII regained control of Paris from the English in 1436, Margaret entered Paris with her husband and permanently settled there at the express request of the king. Little is known of her life after this date and she never had any children. She died on February 2, 1442 after a long illness and was buried in the church of the convent of the Carmelites of Paris. A copy of her will is preserved in the Archives de la Loire Inférieure in Nantes.

E. Cosneau, in his biography of Margaret’s husband, “Le Connétable de Richemont” says this about her:

“The Duchess of Guyenne died in Paris on February 2 (1442). Richemont lost the companion of his youth, of his years of hardship, the one who, widow of the Dauphin of France had by her choice, raised to the highest rank, that which encouraged his ambition, hastened his fortune, faithfully shared his disgrace and seconded his efforts. The role of this princess goes beyond the sphere of the domestic hearth. By working to reconcile her brother-in-law Charles VII with her brother the Duke of Burgundy, by staying in Paris at the preference of the court where she represented the royal family, she rendered service to the king and to France and thus deserves a place in the history of this memorable reign.”

Further reading: “Royal Intrigue: Crisis at the Court of Charles VI 1392-1420” by R.C. Famiglietti, “John the Fearless” by Richard Vaughan, “The Life and Afterlife of Isabeau of Bavaria” by Tracy Adams, “Philip the Good” by Richard Vaughan, “The Role of Women in the Middle Ages” edited by Rosemarie T. Morewedge

[…] elements and surrounded the dauphin with trusted partisans in addition to marrying his eldest daughter Margaret to the dauphin, Louis, Duke of Guyenne in […]

LikeLike

[…] “The Treasure of the City of Ladies” which had initially been dedicated to Margaret of Nevers, Dauphine of France. Her library would become the genesis of the Bibliothèque nationale of […]

LikeLike

[…] was married in 1404 to Margaret of Nevers, the daughter of John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy. As Louis grew older, with the help of his […]

LikeLike

[…] and Margaret of Nevers were married on August 30, 1404 in the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris. They were just children […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on History's Untold Treasures and commented:

H/T The Freelance History Writer

LikeLike

Perhaps in Arthur’s case, his marriages were for politics alone be and he never intended to have children by them? By a mistress, he did have a daughter, Jacqueline, who was legitimised in 1443 during his brief second marriage to Joan of Albret.

LikeLike

A quibble: associating the last battle of the Hundred Years War with the recovery of Paris is a little premature, so I’m sure that’s a typographical error. However, for clarity, this may benefit from expansion.

It took Arthur some years to retrain the French army, create the Ordonnances and transform the royal finances, before he could take Normandy and drive the English out of the North in 1450.

The battle of Castillon in 1453 (the same year that Constantinople fell) secures the South of France. Alan’s nephew Duke Peter led the final cavalry charge.

LikeLike

Fixed it!

LikeLike

I enjoyed reading about Margret. I found interesting all the interconnections.Good work,📣

On Fri, Feb 2, 2018 at 6:30 PM, The Freelance History Writer wrote:

> Susan Abernethy posted: ” A grand-daughter of Philip the Bold, Duke of > Burgundy, Margaret was destined to be a pawn for her family’s political > fortunes. Her life was comprised of many twists and turns. She would become > a consummate negotiator and assist in bringing reconci” >

LikeLike

[…] Origen: Margaret of Nevers, Dauphine of France, Duchess of Guyenne and Countess of Richemont « The Freelanc… […]

LikeLike

Philip the Bold and John the Fearless. What a pair! 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

So sad that Margaret could not have had that so-important accomplishment of royal women; the production of a healthy son. Her value and position as the mother of an heir would have given her more leverage & control of her fortunes. Sadly, as well, her sister produced no Plantagenet heir for Bedford, which did not help England’s fortunes in France. Still, she was remarkable for what she managed to accomplish! Unusual for a childless woman of her times!

So much history was influenced by women’s fecundity! Of course, it was ALWAYS the woman’s fault if she were barren! She bore all the risks and calumny. If a man was “lucky” he could bury a barren wife who died young and try again. Woe to he who was stuck in a childless marriage! How many perfectly healthy women “lost” their lives by “natural” causes due to chronic childlessness?

Women were usually pawns. Fortuna favored she who mothered an heir! So much better opportunity to carve a place for herself & maybe direct some of her own fortunes. Fortunate for Margaret that her brother needed her & her husband found her useful. Good for her! She bucked the norm!

Love reading about the missing half of history; women and their contributions! Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person