Liège was a part of the Holy Roman Empire and had been ruled by prince-bishops since the year 972. The city remained free of interference from the Empire except in the case of the death of a prince-bishop. Because they were celibate, they had no heirs and the successor had to be chosen. Liège was one of the most rebellious medieval principalities in the two centuries prior to its domination by the Burgundian dukes. In the late fourteenth century, the Valois Burgundian Dukes were flexing their might and Liège increasingly came under their control.

Many times the Liègeois were not satisfied with their prince-bishop and resorted to rebellion with the conflicts sometimes lasting for years. The rebellion that ended in the Battle of Othée had begun in 1390 and raged on and off with the people fighting against the principality’s military. John of Bavaria, the ruling prince-bishop, was unsuccessful in trying to vigorously establish and maintain his authority in Liège, to the point of being rash. In 1407, John of Bavaria was compelled to ask for help from his most commanding relative, John, Duke of Burgundy.

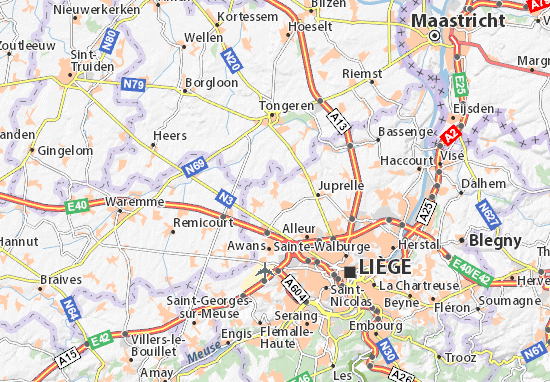

The Duke was delighted to have the chance to end the rebellion. He had an ulterior motive in that he may have sought to demonstrate and establish his own military skill to intimidate his Armagnac enemies in France as well as expand his territory in the Low Countries. As soon as the Liègeois found out about the Duke of Burgundy’s intervention, they started to besiege Maastricht which was loyal to John of Bavaria and had offered him protection. The besiegers made copious use of gunpowder weapons. From November 24, 1406 to January 7, 1408, the town was bombarded with 1514 balls, on average about thirty balls a day. Another lengthy bombardment followed in July and the city was facing deprivation.

Once the Duke arrived, he didn’t come to the relief of Maastricht as expected but marched instead against the town of Liège. The rebels were forced to abandon the siege of Maastricht to try to prevent the invasion of Liège. Negotiations between the Duke and the Liègeois, brokered by the French, delayed any fighting until the middle of September. During this time, the Duke’s army grew and acquired more arms. Records state he had twelve hundred carts full of victuals, war habiliments, and artillery including ribauldequins and coulevrines. Negotiations broke off on September 20 and three days later, the Duke started the siege of Tongeren, one of the leading rebel towns, with bombardment of artillery.

The armies finally met on a field at Othée on September 23. The best account of the battle comes from a letter from John of Burgundy to his brother Anthony, Duke of Brabant. Once the rebel army was within sight, John of Burgundy and John of Bavaria, who was with him, positioned their infantry in one big mass with wings on either side of cavalry and archers. The Duke felt this would be the best formation to oppose any charge against them. He rode a small horse from one part of the army to another, exhorting and encouraging his men.

The Liègeois came forward but stopped about three bow shots away from the Burgundians, came into formation and began firing their gunpowder artillery at the enemy with no hand-to-hand fighting. The gunfire was returned by the Burgundians. The Burgundians stood their ground until the Duke ordered most of his army to advance and attack. He sent four hundred cavalry and one thousand men on foot around the main formations to attack the Liègeois from the rear, while the rest of his men engaged in a frontal assault. They marched one hour after midday in excellent order.

The tactic worked beautifully with the battle only lasting about an hour and a half and the Burgundians prevailing. Men from Tongeren arrived to assist the Liègeois but when they saw the state of affairs on the battlefield, they fled, pursued by mounted Burgundians and many of them were killed. Although the Duke was hit by many missiles and arrows, he didn’t lose one drop of blood. When his men asked him if they should cease from killing the Liègeois, he replied they should all die together and he had no wish for prisoners to be taken and ransomed. The Duke was praised for his bravery and coolness in the battle. The number of dead from Liège may have been as high as eighty-three hundred. The Burgundians lost 212 knights and squires.

The rebels tried to regroup but were unsuccessful. A few days after the battle of Othée, John of Burgundy and John of Bavaria marched to the outskirts of Liège unopposed. From there they extracted revenge by beheading the ringleaders of the revolt and drowning in the Meuse River the ecclesiastics who had defied their prince-bishop. Because of this, John of Bavaria became known as the “Pitiless” and John, Duke of Burgundy earned his soubriquet of “the Fearless”.

The evolution of warfare in the fourteenth century allowed men on foot to more readily determine a winning outcome in battles. Cavalry still served a purpose in scouting, pursuit, shadowing and ravaging but were less effective than infantry at this time. Othée was a great victory for reliable men-at-arms over much larger forces. John the Fearless’ tactics and strategies and use of gunpowder weapons indicate he was an astute military general. He learned how to use guns and used them effectively on the battlefield and in sieges. However, after this battle, his use of gunpowder artillery on the battlefield was limited.

John the Fearless would use the tactics he learned at the Battle of Othée against his Armagnac enemies in the civil war that followed in France. He would write up a description of his plan of battle in September of 1417 where he explains that the infantry tactics he used at Othée were his chosen means of fighting battles. The subjection of Liège was one step in the Burgundian domination and control of the Low Countries and the hatred of John the Fearless by the Liègeois was transferred to his son Philip the Good after his death by assassination by the French Dauphin Charles and his associates in 1419. John of Bavaria would die in 1425. It was rumored he was killed by a prayer book laced with poison.

Further reading: “The Oxford Encyclopedia of Medieval Warfare and Military Technology” edited by Clifford J. Rogers, “The Artillery of the Dukes of Burgundy 1363-1477” by Robert Douglas Smith and Kelly DeVries, “John the Fearless: The Growth of Burgundian Power” by Richard Vaughan, “Philip the Good: The Apogee of Burgundy” by Richard Vaughan

[…] Margaret’s grandfather died that same year and her father became the duke of Burgundy and would be known as John the Fearless. As the king became more erratic in his behavior, the control over Louis as dauphin became […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on History's Untold Treasures and commented:

H/T The Freelance History Writer

LikeLike