The Freelance History Writer welcomes Michael Long. He is a freelance author and historian and has written many articles on medieval and Tudor history mostly in the UK. He has spent more than thirty years teaching history and is presently writing a novel based on the exploits of Willikin of the Weald.

In the summer of 1216, England was a country suffering under foreign invasion. The French under the Dauphin, Prince Louis, the eldest son of King Phillip Augustus, had invaded England to take the Crown from King John. The French invasion of England in 1216 was the culmination of an ongoing struggle between the Plantagenet Kings of England who were also rulers of a vast empire in France and their enemy, King Phillip II of France.

The English-Plantagenet hold on their French Empire was waning. When John became King in 1199, the empire stretched from the Scotish borders to the Pyrenees. By 1216, Normandy and most of the empire had been lost. The country was in the midst of a bitter civil war between the King and his Barons and two-thirds of the rebel Lords supported Louis’ claim to the throne. French armies ravaged the countryside of southern England. Villages were levelled, crops and buildings burned as the French invaders left a path of rape, pillage and destruction in their wake. From the ashes of catastrophe emerged one man, hailed in the chronicles as a national hero and a fighter for English freedom from French aggression, a low-born nobody named William of Cassingham, who became known as ‘Willikin of the Weald.’

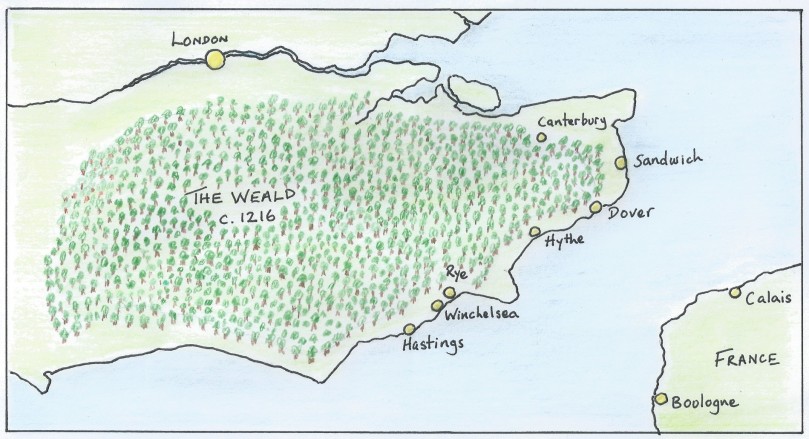

Medieval history was written for the reputation of Kings, Nobles and the Church by patrons who paid for it. Rarely do ‘low-born’ figures feature. Not so with Willikin of the Weald. He established his reputation fighting the French in a guerilla war in the Weald of Kent and Sussex. In the thirteenth century, this stretched from London southwards to the channel coast and from the mainland of Kent west towards the New Forest. Heavily forested and sparsely populated, the Weald became his battlefield attacking the French using skilled local huntsmen and their favoured hunting weapon, the longbow.

One contemporary source, a monk named Roger of Wendover, wrote that William refused to swear loyalty to Louis and gathered one thousand archers and from their isolated camps in the Wealden forests, attacked the French while they were on the move. The figure of one thousand may be an exaggeration. However, William and these men knew the terrain and used it to their advantage. Roger of Wendover records that William, “killed many thousands of them.” The heavily armoured French knights would be ineffective in the forests whereas William’s archers could adopt ‘hit-and-run’ tactics causing maximum damage before disappearing into the trees. Local villages in Kent and Sussex would have witnessed French foraging parties seizing food and animals; Louis’ soldiers engaged in ‘ravaging;’ a policy of terror, killing, rape, theft, burning and torture towards non-combatants. There was no chivalry in their actions. The French labelled William an outlaw and placed a price on his head. But William too engaged in brutal tactics. He and his men took no prisoners; French soldiers who surrendered were immediately executed and beheaded. Long before the concept of guerilla warfare was articulated, William was developing the tactics. They could not afford the men to guard, much less the food prisoners would consume, so execution provided the solution as well as instilling terror into the French already fearful of the forest and the evil spirits which they believed resided there. The French had to use the forest tracks and ancient routes through the Weald to get north from their supply bases on the south coast.

William and his men moved smoothly through the Weald, indicating they possessed extensive local knowledge and giving them a distinct tactical advantage. The chronicles record William returning possessions, looted by the French, to their rightful owners earning him their admiration and thanks. Who then was William of Cassingham? The evidence of his existence and his exploits is very real. Certainly, he was a young man, perhaps under thirty-years-old, for Roger of Wendover describes him as, “ … a certain youth, a fighter and a loyalist.” His origins are unclear, but he may have been a Brabant mercenary, whose men had a reputation for military skills, or the son of one with an English mother. The chronicles do not portray him as a foreigner rather as a loyal Englishman fighting for his King. What is also not clear is where he learned his guerrilla tactics though fighting in France for the lands of his Plantagenet King is most likely the answer.

Both Henry II and Richard I used Brabanter mercenaries in Normandy and John employed them in his war against the Barons. That William had such a familiarity with the landscape of the Weald suggests he grew up there. His military skill indicates experience fighting in a war, most likely in the unsuccessful English defence of Normandy after 1204. He and his men were a highly effective mobile fighting force, who most importantly had the backing of the local villagers who provided safe-havens, supplies and intelligence for William’s resistance fighters.

The author of the “History of William Marshal”, England’s premier knight of the period, wrote, “witness the deeds of Willikin of the Weald,” when it came to attacking the French. A monk from Bethune in northern France wrote in his “Histoire des Ducs de Normandie”, of William, “..noble prowess,” and how he was much feared and “renowned in the Dauphin’s army.” One month before his death in October 1216, King John sent a despatch to William thanking him for his loyal service and paying him for the military campaign against the French.

With John’s death, the Crown passed to his nine-year-old son Henry III, but the power behind the throne was the new Regent, William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke. William of Cassingham swore loyalty to the new King and continued to fight the French. By the autumn of 1216, Louis held three-fifths of England having laid siege to many of its principal castles including Rochester, Marlborough and Berkhamsted. In February 1217, William organised attacks on the French forces around the channel port of Winchelsea. Such had been the impact of Willikin of the Weald on the French army that Louis had to seek reinforcements from France. To land these reinforcements he needed to secure both Winchelsea and the neighbouring port of Rye. Louis had been obliged to lay siege to Dover, and now he was concerned that the route his siege engines had to take drove them straight through the Weald exposing them to surprise attacks from William and his men.

When Prince Louis’ army arrived in Winchelsea, they found an English fleet in the Channel blockading them and William of Cassingham and his men on their flank. Thus the French supply lines from London were cut off. French attempts to send foraging parties to seize food and supplies from local villages were met with a hail of arrows and death, bringing further adulation of William from local people. Despite this, French attempts to force their way through the forest to open the roads to London met with little success. William’s men “ harassed them fiercely” killing more than one thousand French and executing any found alive. Unable to break out of the stranglehold William had imposed, Louis mounted a major sea expedition to rescue his forces.

Louis was not about to give up. His troops were still besieging Dover castle, and Louis attempted to land his reinforcements there to assist the siege. As Louis was trying to land his army at Dover, William and his men launched a surprise attack on the French besiegers camp, burning it and killing many French attackers. Prince Louis was forced to abandon his landing, and he sailed east seeking another landing spot. He settled on Sandwich and in a rage at William’s actions, he sacked and burned the town moving on to Hythe and Romney during the next months which suffered a similar fate. Meanwhile, his army was hemmed in by William and his archers. By the spring of 1217, such was William’s reputation that William Marshal gave him joint command of the army outside Dover along with Oliver Fitzroy, the bastard son of King John.

Forgotten by the history books, William was a tactical genius. Although he did succeed in landing his army on the Kent coast in 1217, Louis’ forces were pinned down by the guerilla campaign waged by William and his men. Roger of Wendover recorded, “all the time they attacked and disrupted the enemy, and many thousands of Frenchmen were slain.” His use of terror unnerved the French, even though the region they were fighting in was ostensibly ‘friendly.’ The French army vastly outnumbered William’s archers but such was his reputation that French soldiers were afraid to venture onto the roads and tracks of the Weald.

By the summer of 1217, Louis’ army had been defeated by William Marshall in a decisive Battle at Lincoln and that August, French reinforcements were destroyed by an English fleet in a decisive naval battle outside Sandwich. Louis was forced to make peace and retreated to France eventually becoming king in 1223 and the civil war in England ended as William Marshal reissued Magna Carta and the rebel lords came to terms with their new King.

Medieval Cassingham is now the small hamlet of Kensham. The contemporary chronicles both English and French and all written at the time, record the actions of William of Cassingham rooting him firmly in the period and indisputably as a real person. That a man of non-noble birth could make such an impression on the chroniclers of both sides is a testimony to the reputation of William as Wiliken of the Weald. His contemporary reputation extended to the King and the nobility as evidenced by his being given the joint command at Dover. His lone stand against the foreign invader made him a national hero. His name was used to inspire; a common born soldier fighting the foreign invader behind enemy lines. With the loss of the Plantagenet empire in France, this was a time of forging a national identity as William Marshal sought to do with his rallying cry at the Battle of Lincoln urging his men to “defend our land.”

With the war at an end, William was rewarded with a pension, estates and royal offices in Essex and Kent including the Wardship of the Seven Hundreds of the Weald. With peace, there were no more battles for the name of Willikin of the Weald to feature in the Chronicles, though his reputation and his legend lived on. William died in the village of Cassingham in 1257. Three hundred years later, the sixteenth-century Holinshed’s Chronicles, the basis for some of Shakespeare’s plays, called William of Cassingham “O Worthy man of English blood!”

It is impossible to read the story of Willikin of the Weald without drawing parallels with the legend of Robin Hood. Robin, for whom there is no contemporary evidence of his existence but the legend of an outlaw archer, leading his men against a hated enemy; living deep in the forest, of which terrain he was a master. In the legend, he lives in the reign of King John; he was seen as a hero by the poor villagers and his reputation went before him. How intriguing that the story of Robin Hood perhaps fits better a real person, rooted in history, England’s forgotten hero, William of Cassingham, the legendary Willikin of the Weald.

Further reading: “L’historie de Guillaume le Marechal” (The History of William Marshal) edited by A.J. Holden, S. Gregory & D. Crouch, “Flowers of History, Comprising the History of England from the Descent of the Saxons to A. D. 1235” by Roger of Wendover (trans. by J. A. Giles), “Histoire des Ducs de Normandie et Rois d’Angleterre” by Anonymous of Bethune, “The Plantagenets” by Dan Jones, “Blood Cries from Afar: The Forgotten Invasion of England” by Sean McGlynn, “A Note on William of Cassingham” in “Speculum Magazine (April 1941)

Thank you Michael for a fascinating read. Of course, the Weald has so many interesting stories and facts associated with it – but this is certainly something I’ve not read about before. From its geology to its history of human habitation, it continues to divulge its secrets. I often stand on Firle Beacon looking north trying to imagine The Weald as it was long ago as one enormous forest. How impressive must that have been? As you probably know, the Romans called it ‘The Forest of Anderida’, and several of their roads can be traced through it. Perhaps there are more roads as yet undiscovered. Perhaps those roads were still visible in William’s time?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciate that this is an old post, but is there any update on Long’s novel, as mentioned in the introductory paragraph?

LikeLike

I’m unable to find any publications on the subject by Mr. Long.

LikeLike

[…] the only one with real plausibility, McGlynn suggests, is William of Cassingham. Otherwise known as Willikin of the Weald, Cassingham led a resistance of bowmen against a French invasion following the days when John […]

LikeLike

Prince Louis’ progress is (apparently) remembered in Surrey (also part of the weald), in the name of the Dolphin pub in Betchworth.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A book well worth reading is “The English Resistance” by Peter Rex. It’s about the underground war against the Norman French.

LikeLike

Louis “a hated enemy”? He was more popular than King John, and it was only the birth of the future Henry III that attracted the barons away from Louis, who then became irrelevant.

LikeLike

Odd thing about Jutish Kent and Saxon Sussex: they have a high proportion of “Celtic” DNA.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Do you know of any articles on the web about this subject – “Jutish Kent and Saxon Sussex: they have a high proportion of “Celtic” DNA”. Doing some amateur research on modern Celtic blood in southeast England.

LikeLike

Check out the website historyfiles.co.uk and https://www.wilcuma.org.uk/kent/the-jutish-settlers-in-kent/ as well as articles in the Encyclopedia Britanica. Bede has some information in his ‘Ecclesiastical History of the English People, readily available in paperback or in PDF online.

LikeLike

This story and it’s background in the Historical Geography of Kent/Sussex is so fascinating. Real places and events that are recorded are so much better than the legends of ‘Robin Hood’ type.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] ‘Willikin of the Weald’: A Forgotten Hero of England ~ A guest post by Michael Long […]

LikeLike

that is I think this is so interesting, as I do all of your articles. I am learning so much about a period of history that I find fascinating.

LikeLike

[…] The Freelance History Writer once again welcomes Michael Long. He is a freelance author and historian and has written many articles on medieval and Tudor history mostly in the UK. He has spent more than thirty years teaching history and is presently writing a novel based on the exploits of Willikin of the Weald. […]

LikeLike

Fascinating; I thought I had a reasonable grasp of our history, but had not heard of Wilikin before. Shame we don’t know what happened to him after all the excitement had died down. Great piece!

LikeLiked by 1 person

William died in the village of Cassingham in 1257. I should have included that perhaps

LikeLiked by 1 person

King John lost the Plantagenet lands in northern France because he starved to death the family of the gaoler of his nephew Prince Arthur, a rival for the throne.

The gaoler escaped to France, where he spread the news that John had murdered Arthur. Poitou, capital province of Aquitaine was already in rebellion; Brittany, Anjou, Normandy and the rest soon followed.

The French king merely caught the apple as it fell from the tree.

Arthur was an heir not only of the Plantagenets but also of the Dukes of Brittany and Earls of Richmond. The first Earl of Richmond, Alan Rufus, was William the Conqueror’s cousin and bodyguard. Alan’s youngest brother Stephen was a grandfather of William de Tancarville, hereditary Chamberlain of Normandy, who was related to William Marshal and both trained and knighted him.

The Marshal supported John over Arthur for superficial reasons, and a close friend told him that he would rue his choice. I think this story may be in the Life of William Marshal commissioned by his son.

LikeLike

I’ve read about him. Love the idea that ‘Robin Hood’ came from my native stomping ground of Sussex.

LikeLike

As I was reading this, I couldn’t help but think of the American Revolutionary fighter Francis Marion. He too fought in an unconventional manner.

LikeLike

The Cassingham name still exists — we’re all related to each other, and trace back to William. There was a U.S. Congressman John Wilson Cassingham (June 22, 1840 – March 14, 1930) from Ohio, which is still a Cassingham stronghold, and plenty of family still in Kent, too.

LikeLike

I’ve read several books and papers discussing the possible identity from whom Robin Hood is drawn, but have never come across this person before. Perhaps because he hailed from the south of England? A very interesting read. Thanks for sharing that.

LikeLike

Weald was still a very isolating place at that time.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That is absolutely fascinating and inspiring. I have never heard of Willikin, although I was born deep in the heart of the Sussex Weald, where my ancestors had lived for centuries.

LikeLike

Wonderful piece of history and one of which I knew little

Thank you

LikeLike