“..the true image of King Louis, her father” Anne “governed him [Charles VIII] so wisely and virtuously that he came to be one of the greatest kings of France.” – Pierre de Brantôme, chronicler

The more I learned about the life of Anne de Beaujeu, the more I came to admire her. Anne inherited a great deal of her intelligence from her father, King Louis XI and was very like him temperamentally. Louis described Anne as the least foolish of her sex in the kingdom of France which contained no wise ones. She was known as Madame la Grande (Grand Madam) and although King Louis never named her official regent, Anne was recognized by the French court and by foreign emissaries as the true ruler of France until her brother declared his independence and she retired to her estates. During the eight years she controlled the government, she adroitly managed to guide the country through a series of political crises that threatened France from within and without.

Anne was the third child but the first to survive beyond a few months of King Louis XI of France and his second wife Charlotte of Savoy. Louis had been at odds with his father, King Charles VII over his marriage to Charlotte during the years of 1454 and 1455. Eventually, Charles raised an army and was going to attack Louis in the Dauphiné where he was residing. Louis took his wife and fled to the court of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy where he stayed in the castle of Genappe in Brabant (what is now Belgium). Anne was born there shortly before the death of her grandfather on July 22, 1461.

Louis quickly returned to France for his coronation. He installed his mother, wife and daughter in the Château of Amboise where they were isolated and not allowed to participate in a royal court or any politics. Anne had a demoiselle d’honneur to watch over her along with at least two chambermaids, several nurses and a cradle rocker. Her mother was in charge of her education. Queen Charlotte had an extensive library and there is every indication Anne read many of these books. They included romances, psalters, books of hours, saint’ lives, devotional works, histories and books on government. There were classics by authors such as Cicero, Boethius, Boccaccio and the works of Christine de Pizan which would serve as a model for the lessons for her daughter which Anne would write later in life. Anne would inherit these books when her mother died and they were in her library at Moulins when she herself died along with other books she had added to her collection.

As soon as her father became king, Anne was the subject of many possible marriage alliances. Potential husbands considered for Anne included King Edward IV of England, Duke Francis II of Brittany, her uncle Charles, Duke of Berry and a potential Aragonese match. When Anne was four, Louis offered her hand to the thirty-two year old Count of Charolais, the future Duke of Burgundy Charles the Bold, perhaps Louis’ most bitter enemy. She was eventually betrothed to Nicholas, Duke of Lorraine. Anne was created Viscountess of Thouars in 1468 in anticipation of the marriage. However, Nicholas broke the engagement to pursue Mary, Duchess of Burgundy and then died unexpectedly in 1473, prompting Louis to take back Thouars.

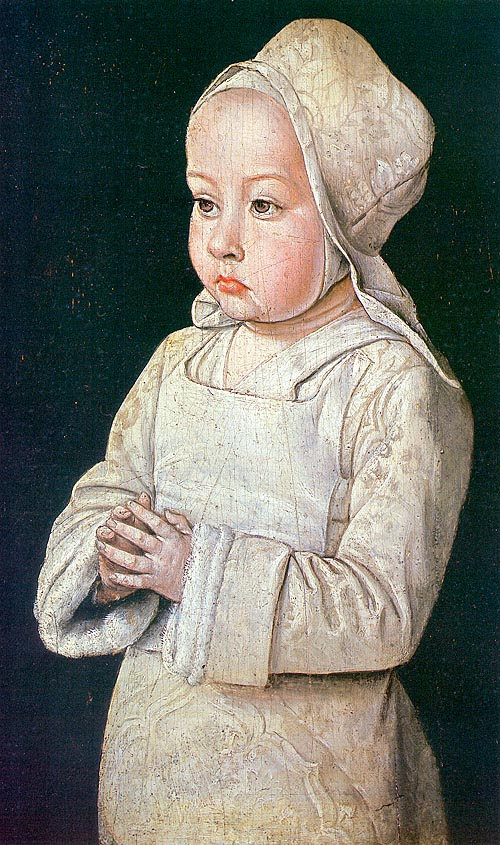

Anne would leave her mother’s schoolroom when she was nearly thirteen to marry the thirty-four year old Pierre de Bourbon on November 3, 1473. Pierre’s brother, the Duke of Bourbon, ceded the title of ‘Lord of Beaujeu’ to Pierre and the couple took up the rule of the Beaujolais. By this time, Anne’s appearance was described as being dark haired with a high forehead, a widow’s peak and finely-arched eyebrows. She stood very erect and straight. Her brown eyes were clear and prominent with a very direct gaze. She had thin lips and hands and a proud nose but wasn’t really considered beautiful. After her marriage, she became a part of court at Plessis-les-Tours and spent much of the next ten years in the company of her father. While in Louis’ entourage she was able to observe up close his methods and approach to the governance of the kingdom. It was during this time Louis began to call her “the least foolish woman in France”.

Anne became pregnant in 1476 but after that there is some confusion as to what happened. The records are inconclusive but a son may have been born, named Charles and given the title of Count of Clermont in 1488, which was the customary name for the heir of the Duchy of Bourbon. He may have died in 1498 and been buried in the family mausoleum of Souvigny. Whatever happened, this was followed by many childless years for Anne.

In 1481, her father gave her the county of Gien as a gift to offset her household expenses and allowing her to be mistress of her own domain. In April of 1483, Anne was sent to Hesdin to fetch the three year old Margaret of Austria and bring her to France to be brought up at the French court and to marry her brother Charles. Later that summer, old King Louis suffered a stroke and was very ill. By this time, most regarded Anne as being in the image of her father. She was twenty-two, an extremely intelligent, shrewd, resolute and energetic woman. Her strong and formidable personality was recognized by her father.

When Louis XI died, he left his thirteen your old son Charles to inherit his throne, ten months short of reaching his majority and ruling in his own right. This meant a regent was required. The obvious candidate would have been his mother Charlotte of Savoy but King Louis had never allowed her to have a role in politics and besides, she was very ill and ended up dying four months after her husband. Another candidate was the First Prince of the Blood, Louis d’Orléans. He had a strong claim to the throne himself but he was politically inexperienced and not highly regarded.

King Louis did not specifically provide the name of a regent but he did require a royal council be formed. He intended to include in the council Charlotte of Savoy, Louis d’Orléans, Duc Jean de Bourbon II and Anne’s husband Pierre. Pierre was the president of the council and Louis also gave the corporeal custody of the king to Pierre and Anne. These unofficial positions gave the Beaujeus great authority. Charles’ birthday passed by, no one was named regent and Anne and Pierre continued in their guardianship of the king and in governing the realm. Anne quickly emerged as the power behind the throne. She had inherited from her father the political wisdom, the resoluteness and the parsimony. But she wielded her power with more tact, better humor and a gentler nature than her father.

France was in a great transition period which had started under King Louis XI. The monarchy was in the process of becoming centralized and the country was beginning to be consolidated and move away from the feudal system. France was still suffering from the material and psychological effects of the Hundred Years War. But Louis had worked very hard to expand the crown demesne and the whole country was subject to the king’s writ. Communications were good, land was being cultivated again and the economy was growing. It was a government that Anne could build on. Anne and Pierre had custody of Charles and the loyalty of the civil service. But they didn’t have the support of the military which was backed by the nobles. And the nobles were expecting an immediate return to feudal policies where they had control over their own fiefs.

Many of the nobles rode to Amboise to pay homage to the new king. Anne was ready with gifts, offices and concessions especially for Louis d’Orléans, the king’s heir and husband of her sister Jeanne. However, she was not ready to concede the guardianship of the king or her position as de facto regent. Louis d’Orléans thought he was the obvious choice for the position of regent and he also wanted a divorce from his wife. He called for a meeting of the Estates General.

Two hundred and forty seven delegates met from January until March 12, 1484 in Tours. Anne was not allowed to attend and she certainly wasn’t allowed to speak to the delegates. Special interest fought special interest. Most of the representatives were more engaged in their own local welfare than the governing of the realm of France. The nobles were politically inept in their attempts to gain control of the boy-king and their own privileges. At least the taxes were lowered even though it was a temporary measure. Anne and her husband held their own, rode out the storm and shrewdly held on to create the strong government Charles would eventually inherit.

The coronation of Charles was celebrated on May 30, 1484. Shortly after this, Louis d’Orléans tried to kidnap the king but Anne spirited him away to Montargis, foiling the plot. Many of Louis’ supporters were dismissed from court and Louis himself retired to his own estates.

As soon as Anne took over management of the court, the expenses of the royal household were greatly increased and continued to go up steeply as long as she was in control. The court never became ostentatious but it was more formal than her father’s, more organized and festive when necessary. She also provided the necessary atmosphere for educating the children of the nobility. Young girls attended her school such as Margaret of Austria, Charles VIII’s wife, Louise of Savoy, and Diane de Poitiers, the future mistress “en titre” of King Henry II. Anne arranged the marriage of Louise of Savoy to Charles d’Angoulême in 1488. These were the parents of the future King François I.

In 1485, Anne gave her support to Henry Tudor against his rival, King Richard III of England. Anne supplied him with money and French troops for his invasion which culminated at the Battle of Bosworth on August 22. Henry emerged as the victor, ascending the throne as Henry VII.

In 1485, Louis d’Orléans once again fomented civil war to gain control of the government. It was called the War of Folly and never gained any traction. Fighting against the Beaujeus festered off and on until 1487. Louis, along with Francis II, Duke of Brittany, and many other French princes conspired to release the king from the Beaujeu’s regency. In June of 1486, Maximilian, King of the Romans, attacked northern France. He was unable to pay his army and they ran out of steam but it created another opening for rebellion among the French princes and Louis d’Orléans joined them.

Anne made peace with the Count of Angouleme and then brokered the Treaty of Châteaubriant with some sixty Breton nobles in March of 1487. The Bretons agreed to serve in the French army. But Anne wanted to annex Brittany to France and was anxious to do so before any foreign aid reached the duchy. She worked hard to raise large sums of money and put the army on war footing. In May, a larger army than was agreed upon in the Treaty invaded Brittany. The army captured many important Breton towns and Louis d’Orléans lost all of his property and all his accomplices were punished by February of 1488.

Pierre’s brother John, the Duke of Bourbon, died in the spring of 1488. Pierre’s other elder brother Charles, who was an archbishop, was Duke of Bourbon for about two weeks before relinquishing the title to Pierre after he took possession of the duchy by force. Anne compelled Charles to sign away his rights for a financial settlement. Anne and Pierre were now Duke and Duchess of Bourbon and ruled over a large swathe of French territory making them the richest and most powerful nobles in France.

In early 1488, the Breton war continued and they managed to gain back a few of the towns gained by the French. The king’s troops were put in the hands of the very capable general Louis de La Trémoille. He recaptured some of the towns along with gaining new ones. He then won a decisive victory at Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier on July 28. Louis d’Orléans along with other Breton nobles were captured. Peace was made but Duke Francis died shortly thereafter, leaving his eleven year old daughter Anne as his heir.

In December of 1488, France again declared war on Brittany and had significant victories. Then Henry VII of England, Ferdinand of Aragon and Maximilian, King of the Romans sent troops to relieve Brittany. This helped the Bretons hang on and Maximilian contracted to marry Duchess Anne and a proxy ceremony took place in March of 1490. Then Maximilian signed a peace treaty in October of 1490 which ended fighting until May of 1491.

When the truce ended, French troops again entered Brittany. The Beaujeus and Louis d’Orléans were reconciled. Anne of Brittany was subject to great pressure while under siege at Rennes and finally was forced to capitulate. King Charles married Duchess Anne at Langeais on December 6, 1491. Margaret of Austria was sent home. Anne de Beaujeu had successfully managed to annex Brittany to France.

Anne only relinquished her power after her husband became Duke of Bourbon. Charles became more independent and Anne directed her attention to her own lands and feudal duties, remaining an advisor to the court. While acting as queen in her own domains, she familiarized herself with the administration of the duchy, reorganized and codified the laws and embarked on a building program. She oversaw the rebuilding of the feudal castle at Gien and built a magnificent new wing at the ducal palace of Moulins to entertain the king and queen. In particular, she loved fountains and collected rare animals and kept them in a menagerie there.

The Beaujeus were able to raise taxes and dispense justice. The Duke and his vassals could raise an army of forty thousand men if needed. Their court was brilliant, they were generous and enlightened patrons. Much to Anne and Pierre’s surprise, Anne became pregnant and gave birth to a daughter on May 10, 1491 who was named Suzanne. Anne of Brittany was crowned on February 8, 1492. Anne carried her train in the procession. When the queen became pregnant later that summer, Anne kept an eye on the queen and was in charge of the arrangements for her lying-in. Charles appointed his sister as regent when he went to war in Italy in September of 1494 at the expense of his wife Anne. During the war he was in financial straits and Anne lent him ten thousand livres in gold plate. She managed to regain half the sum in twelve months by making Charles pay in installments.

When King Charles died in April of 1498, Anne could have made a power play for the throne for herself. Louis d’Orléans’ many rebellions against Charles had not done much good for his reputation and he did not inspire confidence in his subjects. Whether or not Anne wanted the throne, Louis found it expedient to curry her favor and support for his regime. Anne graciously agreed to support Louis even though he immediately divorced her sister. Anne asked for the moon in return. Louis agreed to waive the royal rights to the duchy of Bourbon and to the Auvergne, giving these rights to Suzanne in the event there was no male heir. Anne attended King Louis’ entry into Paris when he became king.

Louis married King Charles’ wife, Anne of Brittany when he became king. Although relations between Anne de Beaujeu and Queen Anne had been somewhat cold, the two women came to appreciate each other after Charles’ death. On March 21, 1501, a contract was signed at Moulins for the marriage of Suzanne to the eleven year old prince of the royal blood, Charles d’Alençon. Pierre meant for this match to safeguard the integrity of the Bourbon inheritance.

In the summer of 1503, the Bourbons, who had been at court, returned to Moulins. During the voyage, Pierre became ill with a fever. They pressed on to the castle where he was racked with fever for two months before succumbing on October 10. Before dying, he had sent for Charles d’Alençon to come to Moulins for his marriage to Suzanne. However, Charles and his mother arrived too late and Charles acted as chief mourner at the funeral.

After Pierre died, in 1504 or 1505, Anne most likely wrote her book of lessons, “Les Enseignements d’Anne de France, duchesse de Bourbonnais et d’Auvergne, á sa fille Susanne de Bourbon”. It was patterned after a book King Louis IX had written for his daughter, a book her father had written for her brother and on the writings of Christine de Pizan. The book is full of traditional advice on the proper behavior of a noblewoman.

Anne managed to break the marriage contract between Suzanne and the Duke d’Alencon. On May 10, 1505, Suzanne married Charles III of Bourbon-Montpensier, Suzanne’s cousin and the next Bourbon male heir. Anne would share the government of the Bourbon realm with her son-in-law. On December 2, 1509, Anne attended the marriage of Marguerite of Savoy, the daughter of Louise of Savoy who had been educated at her court. In October of 1510, Anne was present at the birth of Renee, Queen Anne’s daughter. She arranged for the queen’s lying-in and held the infant at her baptism.

Anne came to witness the funeral of Queen Anne in February of 1514. She graciously comforted the queen’s ladies, honoring each of them with a kiss. Anne kept up her duties at home as well as at court. When King Louis died in January 1515, Anne attended the coronation at Reims of the new king François I. She then rode back to Saint Denis for his official entry into Paris, riding in a litter behind François’ wife Claude and his mother Louise.

Anne’s beloved daughter Suzanne died in April of 1521. Anne herself became ill the next year. A week before her death, she made over to her son-in-law all of her possessions to which she owned personal title. She died on November 14, 1522 in the Chateau of Chandelle, Coulandon. She was buried with her husband and daughter in the abbey of Souvigny.

Anne’s handling of events as a young woman in her twenties is nothing short of astonishing. She was able to assess a situation and either pre-empt it or react in an appropriate manner. She rarely made a wrong decision. When she was eased out of power after the death of her brother, she left the country more stable than when she started her rule which was unusual for a regency. Her attempt to carve out a personal kingdom in the Bourbonnais was counter to the consolidation of the kingdom and would actually come undone when her daughter died childless. She had integrity and moral stature to go along with her political skills. She is a woman who commands admiration.

Further reading: “Queen’s Mate: Three women of power in France on the eve of the Renaissance” by Pauline Matarasso, “A History of France from the Death of Louis XI” by John Seargeant Cyprian Bridge, “Anne of France: Lessons for my Daughter” translated by Sharon L. Jansen, “The Universal Spider: Louis XI” by Paul Murray Kendall, “The Valois: Kings of France 1328-1589” by Robert Knecht, “Encyclopedia of Women in the Renaissance: Italy, France and England” edited by Diana Robin, Anne R. Larsen and Carole Levin, “Francis the First” by Francis Hackett, “Louis XII” by Frederic J. Baumgartner

[…] VIII, Philippa went with her entourage and lived at the court of one of her other relatives, Anne de Beaujeu, Duchess of Bourbon and regent of France. Anne arranged a marriage for Philippa with René II, Duke of Lorraine which […]

LikeLike

[…] men who supported Henry and enhancing his bid for the English throne. King Charles VIII’s sister Anne de Beaujeu, who was acting as his regent saw an opportunity to challenge Richard III and gave Henry money, […]

LikeLike

This is Woman is a hear me quietly roar Woman!Her courage and grace were amazing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] blog articles on the Siege of Rennes, Anne of Brittany, Anne of France, King Louis XII and his quarrel with Anne of France and other topics have been of great value to me […]

LikeLike

[…] For further reading I recommend, Susan Abernathy’s post: Duchess Anne de Beaujeu […]

LikeLike

[…] Susan, “Anne de Beaujeu, Duchess of Bourbon and Regent of France,” Freelance History […]

LikeLike

[…] Susan, “Anne de Beaujeu, Duchess of Bourbon and Regent of France,” Freelance History […]

LikeLike

[…] Edward’s death changed everything for the exiled uncle and nephew. With the collaboration of Henry’s mother Margaret, and money, troops and ships from Duke Francis, Jasper and Henry tried to join the rebellion of the Duke of Buckingham against the new king, Richard III. Their ships were blown off course and they were forced to return to Brittany. In September 1484, Richard was intriguing to capture them from Brittany and they fled to France. King Louis XI was dead and his son Charles VIII was now king but was under the regency of his sister Anne de Beaujeu. […]

LikeLike

[…] was being ruled by a regent, Anne de Beaujeu, sister of the young French king Charles VIII. She was in a struggle with Louis, Duke of Orleans […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Powerful Renaissance Women and commented:

Anne de Beaujeu is one of the major characters the novel I’m currently working one about Anne of Brittany. Another excellent article from the Freelance History Writer.

LikeLike

Wonderful article. Just imagine if women could have ruled in their own right instead very often being a regent.

LikeLike

Yes. Anne should have been queen.

LikeLike

Very interesting article. Just as a sidelight, Anne apparently had a great desire for the Medici giraffe which had arrived in Florence in 1487 and which she believed Lorenzo had promised to her This odd little incident is briefly covered at http://www.artinsociety.com/the-art-of-giraffe-diplomacy.html and in more detail in Marina Belozerskaya’s The Medici Giraffe, p 128

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes I came across that anecdote in my research. Thanks for the link to the most interesting article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You know, when considering all the offbeat, unusual stories I have heard about the Medicis, owning a “Medici Giraffe” probably shouldn’t surprise me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a great article of great information. Thanks a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent work, Susan.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank You very much for another highly informative article! A through delight to read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome Ray!

LikeLike