Stew Ross joins us with a guest post. He is a retired commercial banker, turned author, entrepreneur, and world traveler. Having grown up in Europe, he loves to travel for history and now shares it with others. Stew combines travel and history in his latest books. He and his wife (and traveling companion) Sandy live in Nashville with Lucy their beagle. You can follow Stew’s blog at Stew Ross History Through Travel.

In the early afternoon of 6 October 1789, the king and queen of France, their family, and the royal court left Versailles Palace and returned to Paris. It had been 107 years since a French king and his court had permanently resided in Paris. What precipitated this unlikely relocation?

The day before, a large group of market–women (some say up to ten thousand—commonly known as les poissardes) marched on Versailles. The journey began as a protest of the scarcity of food and in particular, high bread prices. By the time they had reached Versailles, the crowd was calling for the king to return to Paris. The following day, Lafayette convinced Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette to return to Paris with the market–women.

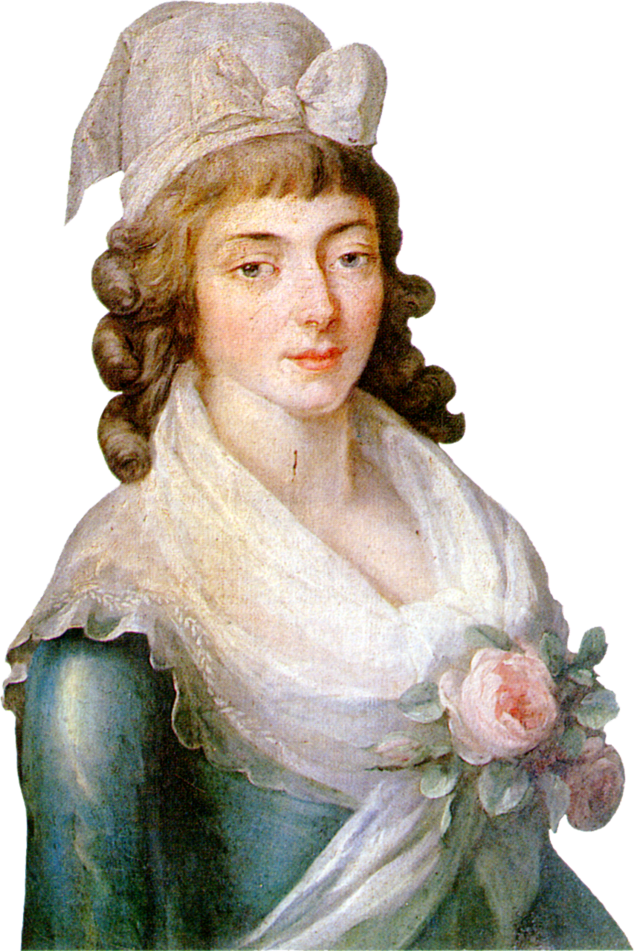

The role of women during the events leading up to and during the French Revolution has been greatly dismissed or glossed over (the exception being the serious historians of the Revolution). Marie Antoinette has always been the iconic woman of the Revolution. It is the queen that has been the subject of movies, books, and the focal point for the general public. However, as we shall see shortly, there were many women who directly contributed to these events (and several who paid for it with their lives).

While most of these women were citizens of Paris, they came from a very diverse background. There were the women of the suburbs (faubourgs—working class), women of nobility (or the aristocracy), women of the burgeoning bourgeoisie (middle class—the merchants), and women of the intelligentsia (the intellectuals). Each group of women had its own set of motivations. For the working class woman, it was based on the survival of her family. For the nobility and aristocracy, it was politically driven (for their survival as a privileged class) while the intelligentsia primarily strove for women’s rights and equality.

On a superficial level, the Revolution is defined in terms of the actions of the king and queen, the male leaders of the Revolution (Robespierre, Danton, and Marat), and The Terror (the guillotine being the primary icon). Yet there were struggles at all levels. The Revolutionary leaders were very aware and even frightened of the expectations of the ordinary citizens, including women (sans culottes—those without knee breeches—extreme Republicans or Revolutionaries). The struggles within and between the political clubs eventually led to the purging of all except the Jacobins. The Girodins and their leader, Madame Roland, would ultimately climb the steps of the scaffold. Women suffragettes such as Théroigne de Méricourt, Claire Lacombe, and Olympe de Gouges would not live to see liberté, équalité, fraternité (freedom, equality, brotherhood) extend to women. It seems the only equitable treatment Robespierre and the Jacobins would grant to women was the opportunity to climb the scaffold stairs.

The Salons

Let’s begin with one of the staples of Parisian society—the salon. No, not a hair, nail, or tanning salon. These were regularly scheduled meetings in the parlors of well-to-do women, typically the nobility and aristocracy (i.e., polite society). The discussions centered on the concepts of the Age of Enlightenment. This was a time when tradition was being replaced by reason and individualism. The season to plant the seeds that would, in time, grow into the overthrow of the French monarchy and the ancien regimé. Anyone who was anyone would be invited to attend. Benjamin Franklin was a frequent attendee as were the future leaders of the French Revolution. It was common to attend multiple salons. Over time, each salon would develop its own political bent and some, like Madame Roland’s salon, would become a political club. By 1793, most of the salons had been suspended or closed down. The Terror was soon to take its vice like grip on the nation. Not until after the Revolution would salons again gain their former popularity.

The salons were the women’s answer to the men only clubs that originated prior to the Revolution. Some of the men’s clubs would morph into Revolutionary clubs such as the Bretons, the Jacobins, and the Cordeliers. Many of the intellectual foundations of these clubs came as a result of their leaders having attended the Paris salons. The salon discussions centered on—among other topics—the various types of government the participants felt France should adopt. One salon in particular became extremely influential. This was Madame Roland’s salon. It provided the seeds for the growth of les Girondins, a political club on par with the Jacobins and Cordeliers.

Madame Roland was an extremely bright individual who as a child, taught herself to read before the age of five. She once said that she felt compelled to read as she felt the need to eat. In the beginning, her salon attracted all of the top members of the Jacobin Club including Robespierre, Brissot, Petion, Buzot, and Vergniaud. All but Robespierre would ultimately form the core of the Girondin Club. Her salon was driven by political discussion (as opposed to other salons that mixed politics with literary and other topics). She enjoyed having an international flair to her salon. Invitations were given to the radical Thomas Paine (England), Helen Maria Williams (England), and Anarcharsis Cootz (Prussian) among others.

Another important salon was that of Madame Condorcet. She hosted one of the more intellectually stimulating salons in Paris. Her husband, the marquis de Condorcet, was one of the leading philosophers and mathematicians of the time. He was one of the strongest advocates for women’s rights and equality, especially for the right to vote. The Condorcets became the first to call for a republic style government. Her salon was known for its very frank and heated discussions. Because of their aversion to the death penalty, Condorcet refused to vote for the king’s death. He was branded as a counter-revolutionary and forced into hiding. Once located, he was arrested and died in prison. Madame Condorcet survived but never regained the status or wealth she enjoyed prior to the Terror.

There were many other salons but one more needs to be mentioned. This is the salon of Madame de Staël. She was the daughter of the very popular finance minister, Jacques Necker. Madame de Stael was known as a brilliant talker—she had a very commanding presence. Her salon was a very influential one and attracted, at one time or another, all of the key players in the Revolution. While being a monarchist at heart, she ultimately embraced the Republic. She tried to stay neutral as long as she could but eventually emigrated to Switzerland where her father had settled. To her dying day, she was an avowed enemy of Napoleon.

The Sans Culottes

On the afternoon of 12 July 1789, upon learning the king had dismissed Jacques Necker, a young man named Camille Desmoulins stood on a chair (or table—not sure if anyone really knows which) outside the Café du Foy and called for the people of Paris to take up arms. Two days later, the medieval fortress known as the Bastille fell to a crowd of approximately 954 citizens. They were the poor, working class citizens from the adjacent faubourg Saint-Antoine. Although the majority were men, the attackers also included women and children. The women who participated in the Women’s March as well as the storming of the Bastille were given special awards by the Revolutionary government. They were given the rank of national heroines or les bonnes citoyennes.

In his book, A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens introduced us to the women who knitted while watching the guillotine perform its job. These women became known as tricoteuses or the knitters. It is not known whether there actually were knitters who attended the executions on a regular basis and given front row seats. However, it is known that faubourg market–women were paid to line the streets and harass the condemned as their tumbrels rolled toward the scaffold.

It is also known that the women citizens participated right alongside the men in the September massacres. This took place over a one-week period in September 1792. Mobs descended on the prisons and brutally massacred a majority of the prison population: men, women, and children.

The Writers

Unlike the male participants of the Revolution, many women wrote written accounts of the Revolution. These include letters, biographies, books, and theatrical plays. Madame Roland wrote her memoirs while in prison waiting her trial and ultimately, execution. Lucy de la Tour du Pin, a lady–in–waiting to Marie Antoinette and émigré, was a prolific letter writer. She chronicled the lifestyle of the court and its members along with the early days of the Revolution. Jeanne Louise Henriette Campan, another lady–in–waiting and reader to the royal children, wrote a biography of Marie Antoinette as well as a descriptive portrait of life at Versailles Palace. Charlotte Robespierre writes about the Duplay family where she and her brother, Maximilien, rented rooms during the Revolution. The list could go on and on and I have undoubtedly neglected to address many other women writers (e.g., Madame de Staël, Madame de Genlis, etc.).

The Feminists

Not only a playwright and ardent feminist, Olympe de Gouges wrote the Declaration of the Rights of Women and the Female Citizen as a response to the National Assembly and the Revolutionary document called the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. She argued that women’s rights were as important as the Revolution’s theme of equal rights. She wrote political pamphlets calling for male–female equality and questioned the male dominance in French society. She was also an outspoken abolitionist of slavery in the French colonies. Unfortunately, de Gouges ended up on the wrong side of Robespierre and the Jacobins. She went to the scaffold on 3 November 1793 at the age of 43.

Although the Society of Revolutionary Republican Women lasted only 5 months, it had a profound effect on the Revolution and its leaders. One of its founders, Claire Lacombe, was part of the mob that stormed the Tuileries Palace on 10 August 1792, effectively ending the French monarchy. Many of the members of the society were sans culottes and radical militants. Soon, the Jacobins feared a massive women’s protest movement would disrupt their activities and banned all of the women’s clubs. Claire was thrown in prison but survived and dies in obscurity.

Théroigne de Méricourt was a feminist and agitator. She seemed to be at all the major events (i.e., Women’s March, attack on the Tuileries Palace, etc.). She also supported the movement for full citizenship for all women. Many women were punished for their active roles and de Méricourt suffered the same fates. She was publicly flogged and then spent the remainder of her life in an insane asylum.

The Revolution produced two significant wins for women: they could divorce their husbands and women could share equally in an inheritance. Unfortunately, a Revolution based on the fundamental ideas of equality and liberty did not extend out its tentacles to embrace women’s rights. But then again, equality for women wasn’t the only loser to come out of the French Revolution.

I you ever get the opportunity to see Lauren Gunderson’s The Revolutionists in the theatre …. run don’t walk! Gunderson is a new playwrighterising to great heights, being named the most producred playwright in the 2017-2018 season. The play is worth seeing …. and reading. Four baddass women of the Terrors: Olympe de Gouges, Charlotte Corday, Marie Antoinette and one composit character from the West Indies, Marianne Angell.

LikeLike

It’s a pity the author mentioned neither Charlotte Corday nor Lucille Desmoulins, Camille’s wife.

LikeLike

It really is such a let down not to see them.

LikeLike

And not a word about Jeanne la Motte Valois, unfortunately. She was amazing and exposed a lot in her books. She suffered from an unfair trial, but did not lose her human dignity. She was awarded the title of honorary citizen of the French Republic. But she was disappointed by the brutality of the revolution and became a socialist .

LikeLike

There was an excellent series of articles about Olympe de Gouges and other feminists during the Revolution, which appeared in Le Point about three or four years ago. Well worth reading.

LikeLike

I find this time in French history to be ghastly, and that means the writer wrote well. k

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Luxury and Queen's and commented:

This is a great post!! Thank you Susan !!

LikeLike

Thanks so much for another wonderful and very educational post. The women of France during the late 18th century were a very intellectual, vocal and brave group of women. I had no idea of that segment of the French Revolution. I will need to read the book.

My real name is Kalli. “Rafter D” is the brand for my cattle and horses and the name of my ranch.

LikeLike

So glad you liked the post Kalli!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had the chance to read this post and I think is a great post.

LikeLike

Stew is an excellent writer and he’s very passionate about the subject.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I totally agree!!!!!

LikeLike

I think he is!!! 😄

LikeLike

Reblogged this on History's Untold Treasures and commented:

H/T The Freelance History Writer

LikeLike